Auction Results Video,

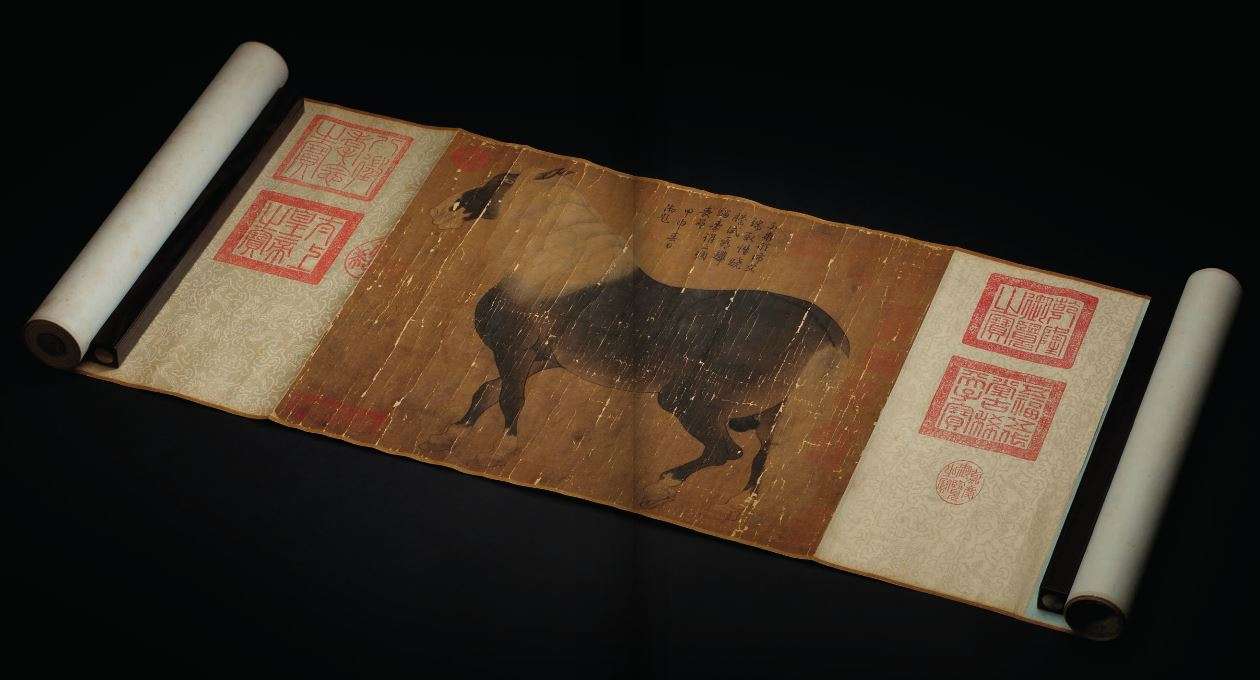

HAN GAN (706-783) AS CATALOGUED IN SHIQU BAOJI Horse Handscroll, ink and color on silk 12 Ω x 15 ¿ in. (31.9 x 38.4 cm.)

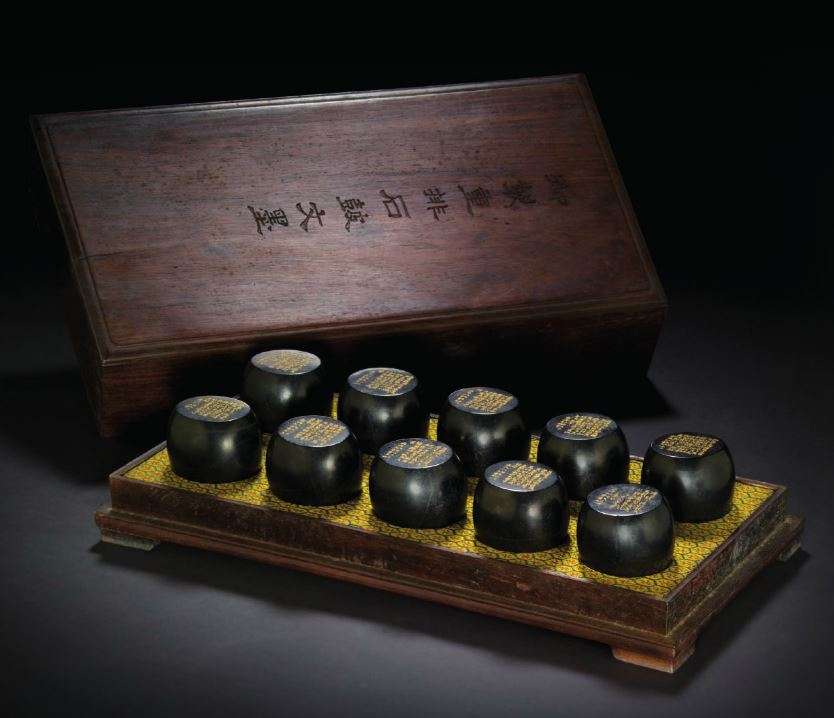

A SET OF TEN IMPERIAL ‘STONE DRUM SCRIPT’ INK CAKES WITH FITTED BOX AND COVER QIANLONG PERIOD (1736-1795)

A MAGNIFICENT AND HIGHLY IMPORTANT BRONZE RITUAL WINE VESSEL, FANGZUN LATE SHANG DYNASTY, ANYANG, 13TH-11TH CENTURY BC

A MAGNIFICENT AND HIGHLY IMPORTANT BRONZE RITUAL WINE VESSEL AND COVER, FANGLEI LATE SHANG DYNASTY, ANYANG, 13TH-11TH CENTURY BC

Ar Asia Week, New York City March 2017

The Fujita Museum Auction, Asia Week 2017

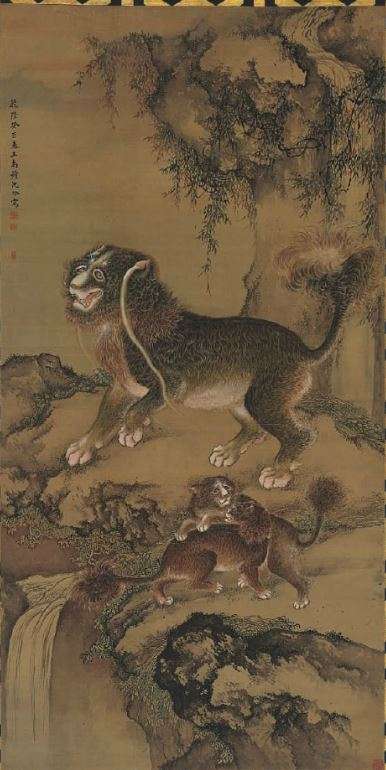

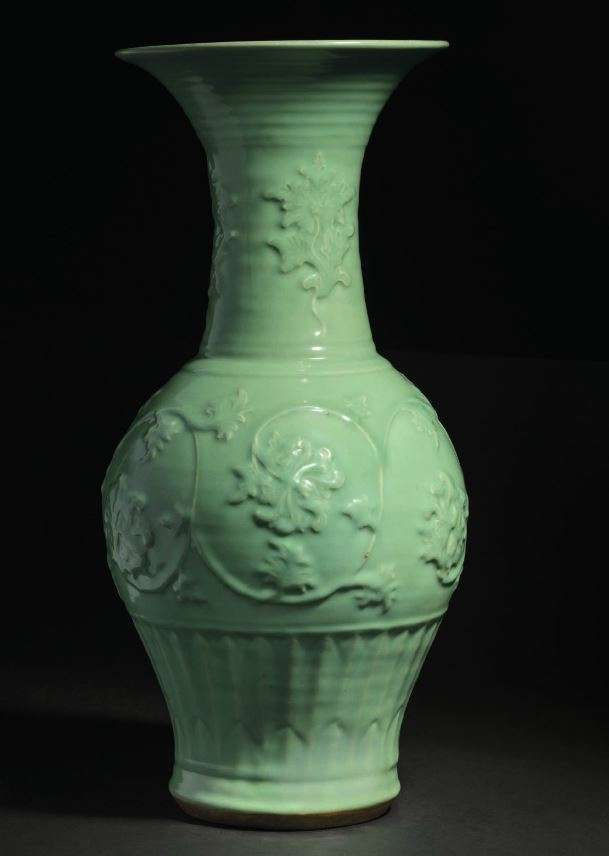

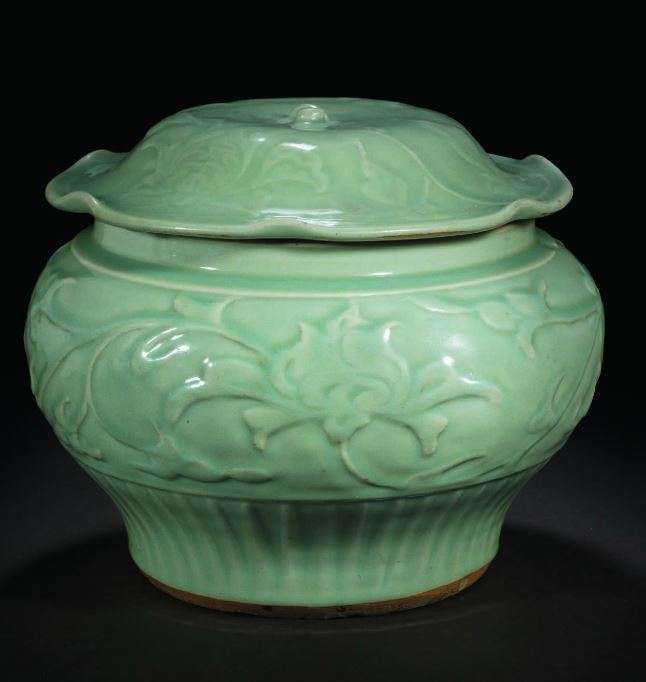

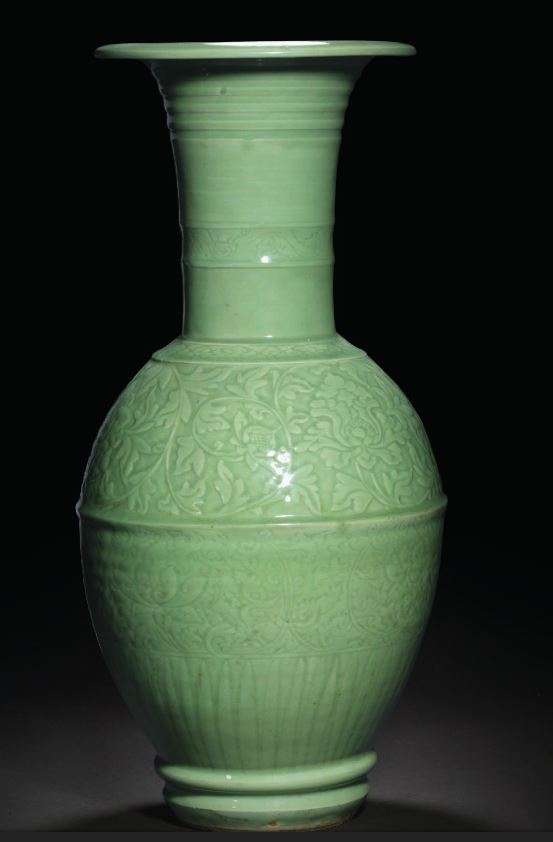

Exceptionally rare Chinese celadons from the Yuan and ming dynasty, fabulous paintings and some of the finest Shang bronzes ever collected.

An Amazing collection.

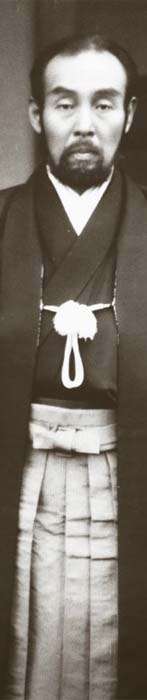

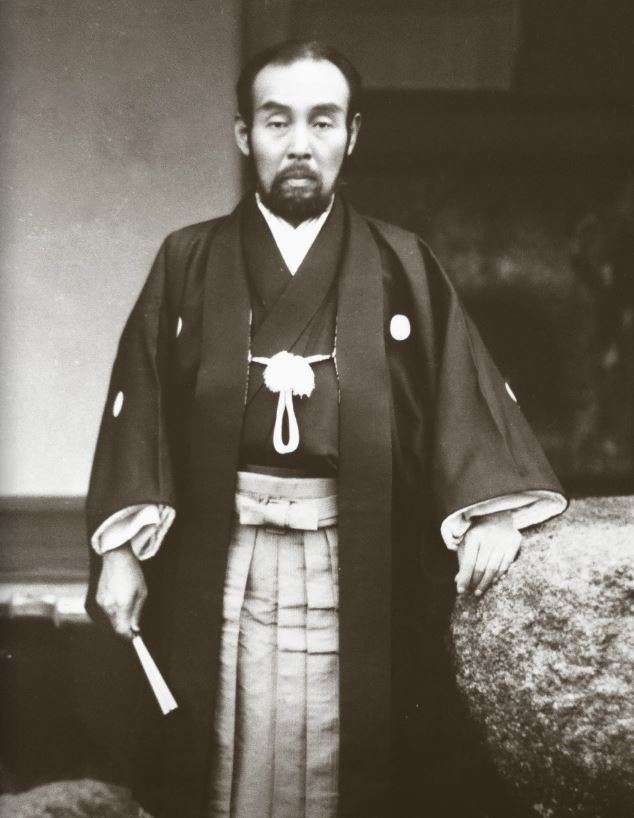

FUJITA DENZABURO ¯

COLLECTORAn except from the catalogue

Fujita Denzaburō (1841–1912) represented the new breed of industrialist collectors in Japan

who emerged in the late nineteenth century. Like his powerful contemporary Masuda Takashi

(1848–1938), the frst director of the Mitsui Trading Company and an early business associate, he was

grounded in traditional Japanese culture and focused on Sino-Japanese arts. As a collector, Fujita was

rough, proud, competitive. He seized every opportunity.Fujita was born in Hagi in Chōshu province (modern Yamaguchi Prefecture), the son of a merchant

family operating a soy sauce brewing business and sake brewery, among other ventures. In 1869, a

year after the Meiji Restoration, he moved to Osaka—noted as a center for wealthy merchants since at

least the seventeenth century—to make his fortune. At the age of about thirty, he had his frst success

selling military footwear to Chōshu warriors who were charged with forming the new army for the

Meiji government. Then, during the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877, working with Yamada Akiyoshi, a

fellow nationalist from Hagi, Fujita made huge profts as a purveyor of military uniforms. That revolt of

disafected samurai from the Kyushu domain of Satsuma was the last in a series of armed uprisings

against the new imperial government.The Japanese people united behind the government’s all-out eforts to catch up with the advanced

nations of the Western world. Fujita branched into business enterprises that helped modernize Japan

at this critical juncture in its history. He had a construction business in Okayama; operated the Kosaka

mine in Akita; and helped establish a newspaper, textile mill, electric power plant and railroad in

the Kansai area. From 1885 to 1889, he was a founding member and the second head of the Osaka

Chamber of Commerce (Osaka Shoko Kaigisho). A distinguished leader of his community, he was also

the frst civilian to be awarded the title of baron (danshaku).In 1909, on his spacious estate in scenic Amijima, Fujita began building three modern, Japanese-style

houses for himself and his two sons, Heitarō—his successor—and Tokujirō. Situated alongside the

Yodo River, in the heart of Osaka City, Fujita’s residence served as headquarters for his business and

political activities. His home was equipped with a Noh stage (he trained in the Kanze School of Noh),

billiard room and some tearooms. Most of the buildings on the property were destroyed during the fre

bombing of Osaka in 1945. Only a seventeenth-century wood pagoda and—miraculously—the three

large storehouses with his art collection survived. The collection is housed today in a small museum

on the Fujita property that opened to the public in 1954. The garden is dotted with an artifcial

miniature hill, waterfall, gorge and pond, as well as some ffty cornerstones of ancient Nara-period

temples and some stone pagodas and lanterns of the Kamakura period.For the elite new collector (the new daimyo, as Christine Guth calls such men), Chinese tea wares

were highly sought after. The Fujita family, for example, paid ¥200,000 for a globular Chinese tea

caddy once owned by the seventeenth-century calligrapher Shōkadō Shōjō, a gigantic increase over

the ¥2,000 it brought when the Sakai family bought it in 1871. (For the purpose of comparison, in

the 1870s, the monthly salary of high government oficials averaged between ¥350 and ¥500. (See

Christine M. E. Guth, Art, Tea and Industry: Masuda Takashi and the Mitsui Circle [Princeton University

Press, 1993], p. 134.) A master of the tea ceremony, Takahashi Sōan (1861–1937), observed that

Fujita would never ask the price of an object he was ofered. Dealers arrived daily with their wares

and spread them out in front of their client, “from whose mouth only two responses emerged: ‘I will

take it’ or ‘ I don’t need it.’ (For more about Sōan and Fujita, see Kumakura Isao, “Chigusa from the

17th Century to 1929,” in Louise Allison Cort and Andrew M. Watsky, eds., Chigusa and the Art of Tea

[Freer|Sackler, 2014], p. 184.)In 1912, desperately ill, Fujita bid from his hospital bed on a tiny, Ming-dynasty ceramic incense

container, a fne example of Kochi ware, yellow with brown and green markings. It had passed through

the hands of the Inaba family in Yodo and the Ikushima family in Kobe. Fujita had his loyal agent Toda

Rochō (Yashichi, 1867–1930) bidding for him at this dealers’ auction. The frst bid was ¥73,000. Fujita

countered by immediately jumping to ¥90,000—the winning bid. Ten days later, he died. Ironically,

the incense container is in the auspicious shape of a tortoise, symbol of longevity (see Maeno

Eri, “ ‘Korekutaa—Fujita Densaburō no shimbigan’ ni yosete” [On the subject of ‘Collector: Fujita

Densaburō’s aesthetic sense’] Tosetsu 704 [Nov. 2011], pp. 23–24).

Fujita spent a fortune on tea utensils, had several rooms designed for the tea ceremony and diligently

studied tea, frst with Mushakojisenke and then with Omotesenke teachers. However, the chanoyu

historian Kumakura Isao discovered that Fujita was not a typical man of tea. Surprisingly, he rarely

hosted tea gatherings at his home, claiming that he had not yet assembled the full range of utensils

necessary for a tea event. Perhaps he felt himself to be inadequate as a practitioner.In Japan, it is customary for collectors to work through only one, sometimes two, dealers, who have

exclusive access to them. Fujita Denzaburō worked with two fabled local dealerships. Until World

War II, the Fujita family acquired Chinese art exclusively through Yamanaka & Company and relied

on Tanimatsuya, or Toda Gallery, for Japanese art and tea wares. Both of these dealerships had their

headquarters in Osaka.Tanimatsuya was founded around 1700, and the Toda family was soon appointed the oficial tea

utensil store (Goyo dogusho) to Matudaira Fumai (1751–1818), the head of the Matsue clan and a

renowned man of tea. Rogin (b. 1843), the eighth head of the Toda family, saw the collapse of the

tea market in the fnal years of the Tokugawa regime, when daimyo patronage ended, but he soon

rejuvenated the business. He adopted Rochō in 1879 from the Toda branch family in Kyoto and trained

him as the ninth head of Tanimatsuya. Together, they developed their business through the period

of Japan’s modernization, from Meiji into the early Shōwa era, working hard to build the great Fujita

family collection on a scale that would be unthinkable today.

The original collection formed by Fujita Denzaburō numbered over seven thousand items (some

say ten thousand), recorded in twenty-fve volumes of what was originally a much larger number

of inventory books dating from 1904, the Kōsetsusai zohin mokuroku (Inventory of the collection of

Kōsetsu; Kōsetsu was one of the collector’s go, or art names). The remaining volumes of the inventory

were lost. In 1929, in the wake of a worldwide depression that hastened the dispersal of many old

collections in Japan, and after the Fujita-owned bank had failed, the family deaccessioned four

hundred important works at a dealers’ auction on the Fujita property. The sale, including two days of

previews, was supported by a long list of eminent art dealers, represented frst and foremost by the

biggest players in Osaka, Yamanaka & Company, as well as Toda Rochō.At that 1929 sale, the Fujita family parted with the Chinese tea-leaf storage jar known as Chigusa

for ¥2,000. In 2009, the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC purchased Chigusa at auction at

Christie’s, New York, for $662,500, well above the estimate. (Fujita had purchased the jar in 1888 from

a Kyoto chanoyu family, the Hisada, who treasured it for 250 years.) There were three additional Fujita

auctions; altogether, the family sold some 860 pieces between 1929 and 1937.Today, the collection formed by Fujita Denzaburō and his sons still numbers five thousand works of

Asian art, including masterpieces of Japanese art, as well as Chinese painting, bronzes, sculpture,

ceramics (most famously, a stunning Chinese tenmoku tea bowl with oil-spot glaze that is now a

designated National Treasure) and decorative arts such as lacquer, jade and textiles. There are nine

National Treasures and ffty-one Important Cultural Properties. The 1972 publication Masterpieces of

the Fujita Museum of Art singles out nearly four hundred of the most important pieces from the Fujita

Collection, including some of the Chinese works of art that are here ofered for sale by Christie’s.

The Catalogue, Click the image to open and vuew

The Catalogue, Click the image to open and vuew

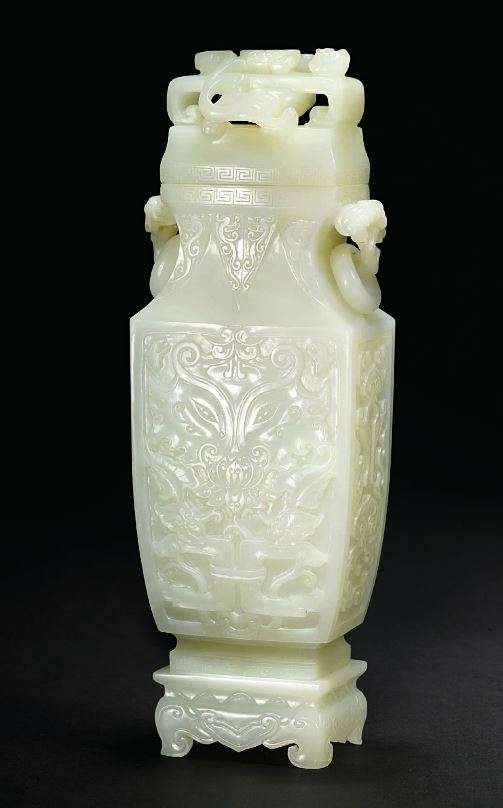

Looking to get information on a Large Chinese Bronze artifact vase with lid