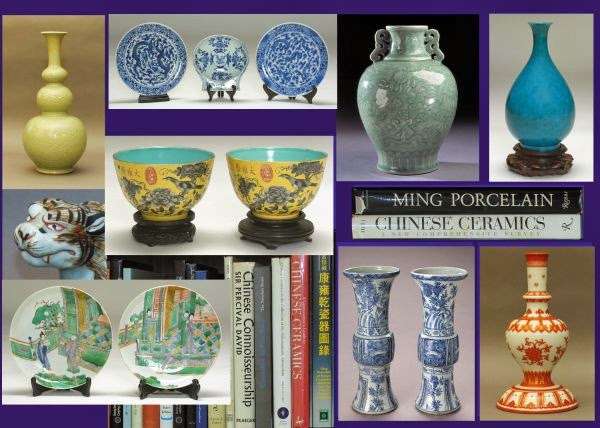

Bidamount News February 20, 2026, Vol 620

Share this post:

Figure 1Vase, Jingdezhen, China, 1300–1330. Porcelain. H. 11 1/4". (Courtesy, National Museum of Ireland, Dublin.)

Ronald W. Fuchs II

A History of Chinese Export Porcelain in Ten Objects

All objects tell stories about technology, design, trade, and consumption, but few are as voluble as Chinese export porcelain. Though hardly central to world history, it lies at the heart of issues that are central. Demand for Chinese porcelain helped fuel European exploration and exploitation, build a global economy, spark experimentation that led to advances in other ceramics traditions, and change the way people drank, dined, and decorated their homes all over the globe.

From the time it was developed, circa A.D. 600, Chinese porcelain has been regarded as one of the finest ceramics produced. “There is nothing like it in European pottery, either from the standpoint of the material itself or its thin and fragile construction,” admitted Matteo Ricci, a sixteenth-century missionary to China.[1] Chinese porcelain was exported to every inhabited place on earth, and it has been prized in one way or another by every culture that has encountered it. Some scholars have suggested that it was one of the first globalized commodities.

Chinese porcelain has even assumed a cultural identity; it is a simile for rarity—“rare as a Ming vase”—and a metaphor for fragility. On the eve of the American Revolution, Benjamin Franklin compared the British Empire to a “noble China Vase...that being once broken, the separate Parts could not retain even their Share of the Strength or Value that existed in the Whole.”[2] The country’s name has even become synonymous for porcelain, one of its most famous products.

From the time of its first importation into Europe, in the fourteenth century, through the nineteenth century, more than seventy million pieces of porcelain were brought to Europe and the Americas.[3] Over this six-hundred-year period, Chinese porcelain has played many different roles as its function, value, and meaning changed.

Through an examination of ten objects I hope to tell the multifaceted history of Chinese export porcelain from 1300 to 1900. Some of the pieces, like the earliest piece of porcelain known to reach Europe, I chose because of their rarity; others were chosen for their owners, like the piece that belonged to George Washington and Robert E. Lee; some are representative examples of the themes they illustrate, like the piece decorated with scenes of the different stages of porcelain production. My selection of objects has been somewhat arbitrary; I could have easily picked others. But these are objects whose stories I find particularly appealing, and together I think they convey at least part of the history of this fascinating material.

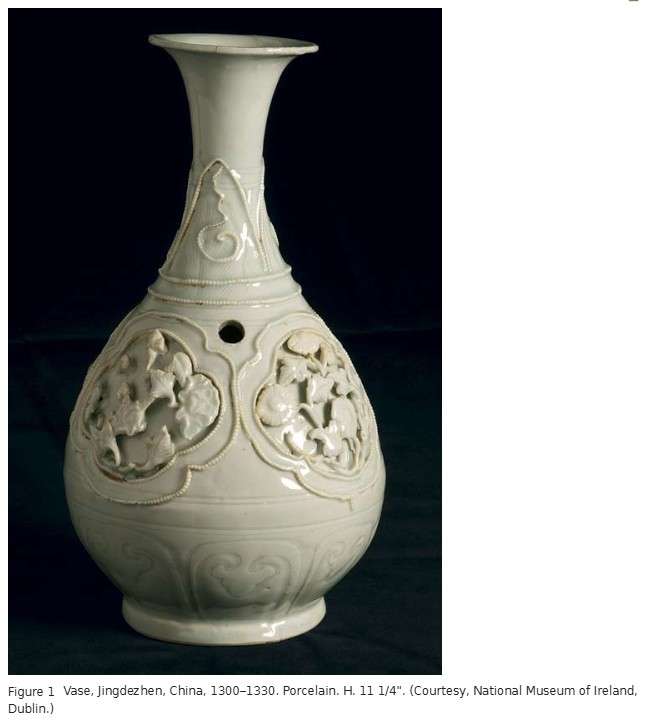

Vase

This vase (fig. 1) is, in general, a fine but unremarkable example of porcelain made in the fourteenth century. What makes it extraordinary is that it is the earliest documented piece of Chinese porcelain known to have reached Europe. It was there by 1381 and, over time, it has been physically modified and its identity lost as the use and meaning of Chinese porcelain changed.

This vase is thought to have come to Hungary in 1338 as a gift to Louis the Great (1326–1382) from a group of Nestorian Christians traveling from China to Avignon to meet Pope Benedict XII. It was definitely in Hungary by 1381, when Louis the Great gave it to Charles III, king of Naples (r. 1382–1386).[4] At this time it was embellished with silver-gilt and enameled mounts, including a handle and spout that transformed it into a ewer. Mounts visually and literally enhanced the value of porcelain, and also transformed it into something more useful to its European owners.[5]

During this period, porcelain was an exotic and wondrous curiosity; its real material and methods of manufacture—even place of manufacture—were barely understood. In addition to being prized for its craftsmanship and exotic origins, its appeal may have had an additional, more practical, consideration: according to some, “if some evil people should soil it [a porcelain vessel] with poison to harm anybody it would instantly break of itself and fall to pieces rather than tolerate the evil beverage which was meant to injure our insides.”[6]

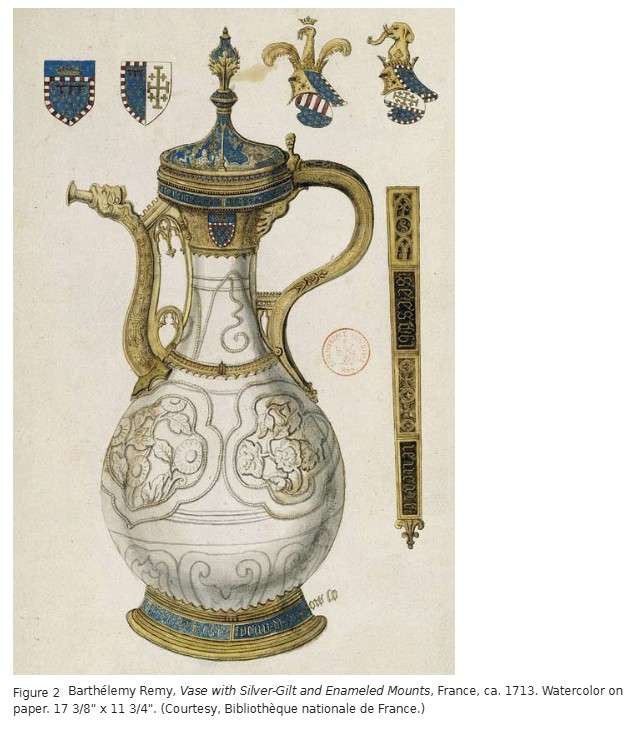

By 1416 this vase had moved to the Kunst- und Wunderkammer (chambers of arts and wonders) of Jean, duc de Berry, of France, and by 1689 it was in the collection of Louis, the Grand Dauphin (1661–1711), heir to Louis XIV. From him it passed to Bishop François Lefebvre de Caumartin (1668–1733), who in 1713 allowed François Roger de Gaignières, an antiquarian, to have it recorded in a watercolor (fig. 2).[7] Thus the vase assumed a new identity as an antiquity, now prized for its age and historical associations.

It was probably for these reasons that the vase was acquired after the French Revolution by the English collector William Thomas Beckford (1760–1844).[8] It was included among “the rarest articles of virtue” in one of the guidebooks to his mansion, Fonthill Abbey.[9] When it was advertised for sale in 1822 it was described as “a bottle of pale sea green oriental china of great antiquity...further curious being the earliest known specimen of porcelain introduced from China into Europe.”[10] By 1882, however, it had lost its mounts, which were probably removed by a thief, and its history had somehow been forgotten. In that year it was acquired by the National Museum of Ireland, where it remained unnoticed until 1959, when Arthur Lane, the keeper of ceramics at the Victoria and Albert Museum, reunited the damaged vase with its long history.[11]

Since then it has been prized as an example of the long connection between China and Europe and of the long fascination that people have had for Chinese porcelain.[12]

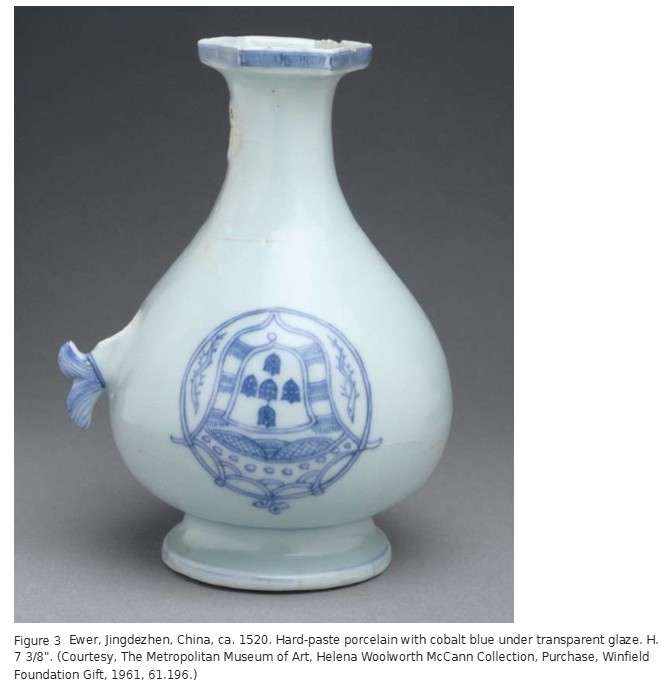

Ewer

When you order something, there is always the risk that it will not turn out the way you expected. That is what happened with this ewer (fig. 3). It is decorated with the coat of arms used by Manuel I of Portugal (r. 1495–1521), but the arms are upside down. Though no doubt a disappointment to the person who commissioned it, it is one of the earliest pieces of Chinese porcelain decorated with a European design and provides clues as to how export porcelain was designed and made.

Desire for such Asian luxuries as spices, textiles, and porcelain drove Europeans to establish direct trade with China, Japan, India, and Indonesia, lands they collectively called “the Indies.” The Portuguese were the first, reaching India in 1498 and China in 1513. It was a world-changing event; English economist Adam Smith wrote without much exaggeration that “the discovery of America, and that of a passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good Hope are the two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind.”[13]

Though Portugal did not establish a trading post in China until 1557, porcelain began to flow in increasing quantities back to Portugal, either bought in India or Indonesia or acquired during illegal voyages to China itself. Most was porcelain designed for the Chinese domestic market or for Asian export markets, but some Portuguese did find a way to commission pieces decorated with European designs.

This process was fraught with difficulty, however, as Jorge Cabral, captain of the Portuguese trading station in Malaysia, discovered. In a 1528 letter to King João III of Portugal (r. 1521–1557) he reported, “last year I asked a captain of the chins [Chinese] that came here to have some pieces made for Your Highness. He brought them, but they are not as I had wished.”[14]

Cabral could have been describing this very ewer, as its upside-down coat of arms is certainly not what someone would have wished. It is easy to imagine how unclear instructions from the Portuguese and Chinese ignorance about the culture of their new trading partners could have resulted in the mistake; a simple explanation could be that no one wrote which end was up on the drawing of the arms given to the Chinese painters.

Such mistakes are actually quite rare in Chinese export porcelain, and this ewer, even though it has lost its spout, is a valuable reminder of how European and Chinese merchants and craftspeople negotiated the difficulties of different languages, cultures, and customs to create successful and marketable pieces of Chinese export porcelain.

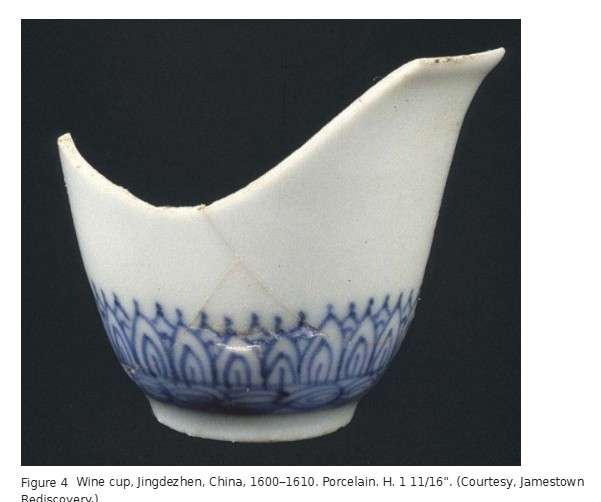

Wine Cup

This tiny cup (fig. 4) is a symbol of the emergence of a global economy at the turn of the seventeenth century. It was used, broken, and discarded circa 1610 in Jamestown, Virginia, the first successful English settlement in North America.

The cup was probably owned by one of Jamestown’s wealthy colonists, a “gentleman,” who would have used it for drinking distilled wine such as brandy, which was known in the period as aqua vitae, or “water of life.” It is among a dozen similar cups dating to between 1610 and 1640 that have been found in Virginia.[15] The presence of porcelain in a struggling settlement on what was, to Europeans, the edge of the known world shows just how desirable a commodity Chinese porcelain was.

The Dutch, who came to dominate European trade with China in the seventeenth century, built a vast trading network that moved goods among Europe, Asia, and the Americas. This they did under the auspices of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (United East India Company of the Netherlands, often known by its initials, VOC), chartered in 1602 and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. By importing ever-larger quantities, and by commissioning Western shapes that could be integrated easily into European drinking and dining practices, the Dutch turned porcelain from an exotic and somewhat esoteric rarity into a luxury that was expensive but readily obtainable. Hence the market for porcelain broadened, so much so that by 1614 one commentator could write that in the Netherlands porcelain is “in nearly daily use with the common people.”[16]

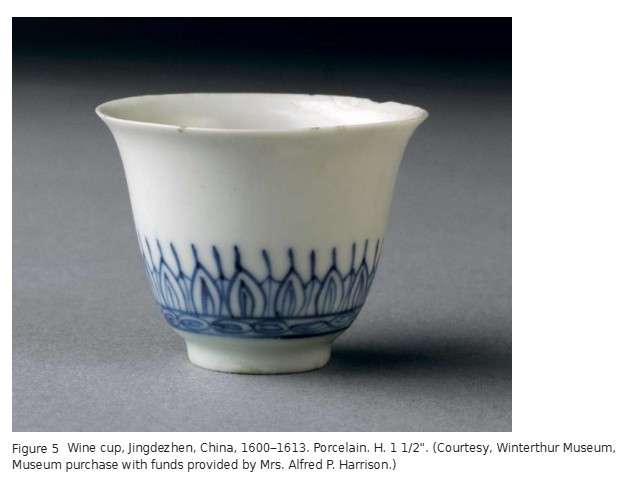

These finely potted cups must have been among the most common types of porcelain exported to Europe in the first decades of the seventeenth century (fig. 5). By 1619 officials in Amsterdam were begging their agents in Asia not to send any more “because the country is full of them.”[17] Despite the oversupply, cups like this continued to be exported until the 1640s, when civil war in China disrupted porcelain production.

The Jamestown cup probably came from China to the Netherlands and from there to England, where it was acquired by one of the colonists who brought it to Virginia. It is possible that the cup came directly to Virginia via a Dutch ship; the Dutch were certainly there by 1619, when they brought the first enslaved Africans to Virginia, but might have been trading in Jamestown as early as 1611.[18]

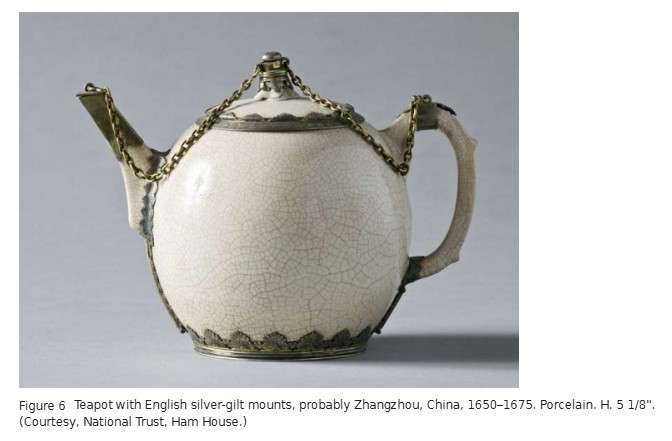

Teapot with English Silver-Gilt Mounts

This teapot (fig. 6) is among the earliest known to survive in Europe. Made between 1650 and 1675, it is thought to have belonged to the Englishwoman Elizabeth Murray (1626–1698), Duchess of Lauderdale. Sophisticated, wealthy, and well connected, she was a regular at the court of Charles II (1620–1685), whose wife, Catherine of Braganza (1638–1705), is often credited with popularizing tea in England.[19]

Tea was first encountered by Europeans in the sixteenth century and began to be imported to Europe in the early seventeenth century. The first recorded shipment to the Netherlands took place in 1610, and by 1637 the directors of the VOC had written their agents in Asia that “as tea begins to come into use by some of the people, we expect some jars of Chinese and Japanese tea with every ship.”[20]

These early shipments most likely were used medicinally, but by the mid-seventeenth century, tea, often sweetened with sugar that was increasingly available from the Caribbean, was popular among wealthy and sophisticated people, such as the Duchess of Lauderdale. Where the aristocracy led, others followed. In 1660 Samuel Pepys, a wealthy but nontitled government official, first tried “a Cupp of Tee (a China drink) of which I had never drank before.”[21] By 1751 another English commentator noted that “The people here are not without their Tea, Coffee, and Chocolate, especially the first, the Use of which is spread to that Degree, that not only the Gentry and Wealthy Traders drink it constantly, but almost every Seamer, Sizer and Winder [low-paid textile workers] will have her Tea and will enjoy herself over it in a Morning.”[22]

But drinking tea was not just about enjoying a warm, caffeinated beverage; it was also about stuff. It was an opportunity to show that you had the knowledge, taste, and wealth to have the right equipment, something well understood by François, duc de La Rochefoucauld, who noted in 1784 that tea drinking provided “the rich with an opportunity to display their magnificence in the matter of tea-pots, cups and so forth.”[23]

In many cases, these “tea-pots, cups and so forth” were made of Chinese porcelain, which was seen by many as a natural accompaniment to Chinese tea. The Duchess of Lauderdale went even further, decorating her private closet at Ham House in Asian style, complete with a “japan box [for] sweetmeats and tea” and a “Tea table carv’d and guilt [sic]” made in Java or Myanmar to provide an appropriate setting for her exotic teapot.[24]

Unlike the majority of export porcelain, this teapot was not made in Jingdezhen but probably in Zhangzhou, in Fujian province, where porcelain was made in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. Thickly potted and almost crude by comparison to Jingdezhen wares, it nevertheless was exported to Japan, Southeast Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

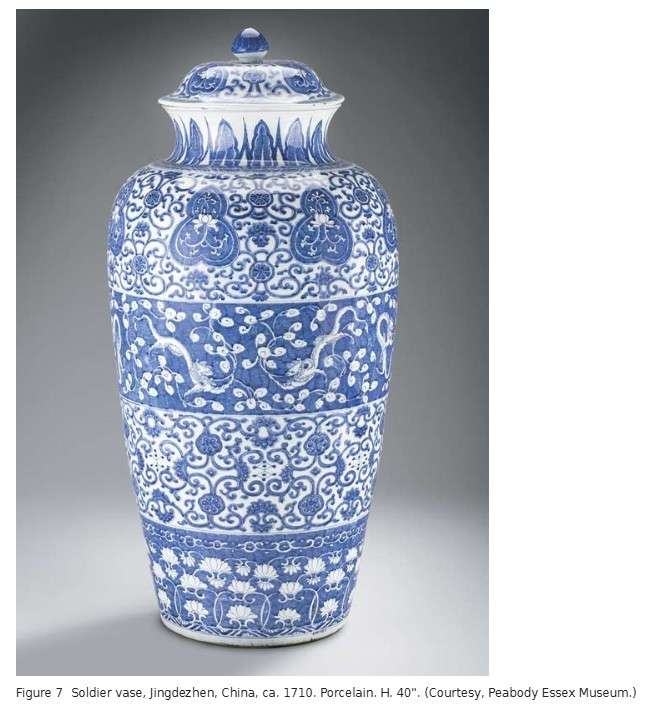

Soldier Vase

Collectors often get carried away with their passion for what they collect. One of the most obsessed collectors of Chinese export porcelain was Augustus the Strong, elector of Saxony and king of Poland (1670–1733), who amassed a collection of some twenty-one thousand pieces of Chinese and Japanese porcelain. He wrote of his obsession, “do you not know that it is the same with the oranges as with porcelain? Namely, that those who have one sickness or the other never believe that they have enough but always feel that they need to have more?”[25]

This obsession led to one of the most famous and bizarre acquisitions of Chinese porcelain of all time: in 1717 Augustus traded 600 of his dragoons—mounted infantrymen—for 151 pieces of porcelain from Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia. Among the pieces was this vase (fig. 7), which was one of a number of oversized vases that became known as “dragoon” or “soldier vases.”[26]

As the China trade became more established in the late seventeenth century, the amount of Chinese porcelain coming into Europe increased. Where before it had been hard to get more than a few pieces, it was now possible to build extensive collections. Large, showy, and expensive pieces like soldier vases were a mark of a collector’s wealth and sophistication. In addition to those owned by Augustus and Friedrich (who kept several), similar vases were acquired by numerous European royals and aristocrats and even by wealthy merchants. Richard Gough, a British East India Company merchant and the uncle of Harry Gough (see below), bought a set of three in 1692.[27]

Not just a status symbol, soldier vases are also a testament to the skill of Chinese potters. François Xavier d’Entrecolles (1664–1741), a French Jesuit missionary who visited Jingdezhen in the 1710s, described how difficult they were to make:

I have however seen Designs executed which were said to be impracticable; these were Urns above three Foot high without the Lid, which rose like a Pyramid a Foot high; these Urns were made of three Pieces, but joined together so neatly that the Place of their Union could not be discover’d; I was told that at the same time that out of twenty-four eight only succeeded: These Works were bespoke by the Merchants of Canton for the European Trade.[28]

If owning a large collection of Chinese porcelain was a status symbol, the ability to make it was even more prestigious. Europeans had tried to make porcelain since the sixteenth century, but it was not until 1708 that Johann Friedrich Böttger, an alchemist, and Ehrenfried Walter von Tschirnhaus, a scientist and court official, working under the patronage of Augustus, developed true porcelain. By 1710 a manufactory had been established at Meissen near the Saxon capital of Dresden that produced a range of wares, many of which were direct copies of pieces of Chinese porcelain from Augustus’s collection. Meissen’s triumph was celebrated in a ceiling painting intended for the throne room of the Japanese Palace, built by Augustus to house his porcelain collection. The painting shows Minerva judging between Asian and Meissen porcelain and declaring Meissen the winner.[29]

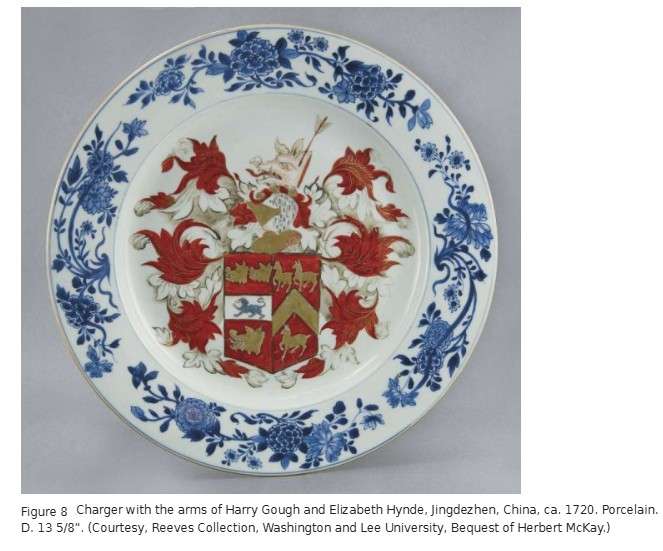

Charger with the Arms of Harry Gough and Elizabeth Hynde

If you wanted to make your fortune in the seventeenth, eighteenth, or nineteenth century, one of the best ways was to go into the China trade. The risks were great, but the opportunities for young, smart, ambitious men (and those active in the China trade were almost all men) to make their fortunes and rise in the world were enormous.

One such success story is the Englishman Harry Gough, who owned this large dish (fig. 8), decorated with his coat of arms impaled with those of his wife, Elizabeth Hynde. Gough worked for the United Company of Merchants Trading to the East Indies, better known as the East India Company. Chartered in 1600, over the course of the eighteenth century it grew to be the largest corporation the world had ever seen. It boasted a monopoly on all British trade with Asia; controlled vast swaths of territory, including much of the subcontinent of India; and created tremendous wealth, especially for its officers, employees, and investors.

Born in 1681, Gough began his career at the age of eleven, when he traveled to China as the assistant of his uncle, Richard Gough. By 1707 he was captain of his own ship, the Streatham, which he commanded until 1715.[30] As an officer of the East India Company, Gough was allowed to participate in the private trade. Although the company had a monopoly on trade with Asia, as a perk of employment it allowed its employees to buy and sell goods for their own profit, the amount depending on their rank. With careful purchases and a little luck, a captain could make a fortune. Gough’s uncle Richard, for instance, “raised a considerable estate from the small stock of a younger brother’s fortune, by the India, and China trade.”[31]

Gough’s profits allowed him to “acquire a decent competency,” which in turn allowed him to retire from the sea. He used his newfound wealth to establish himself as a member of the gentry by purchasing an estate in Warwickshire in 1717, being elected to Parliament in 1734, and serving as a member of the board of directors of the East India Company from 1730 to 1751.[32]

One of the ways Gough showed off his new status was by commissioning a set of armorial porcelain. Increasingly popular from the late seventeenth century, armorial porcelain was a way to demonstrate one’s wealth, status, and family heritage. It was especially popular among newly rich China trade merchants, who could easily commission dinner services through colleagues or during their own trips to China. Harry and Elizabeth Gough had at least three services of their own, and a fourth with the Gough arms may have belonged to them or to one of their relatives.[33]

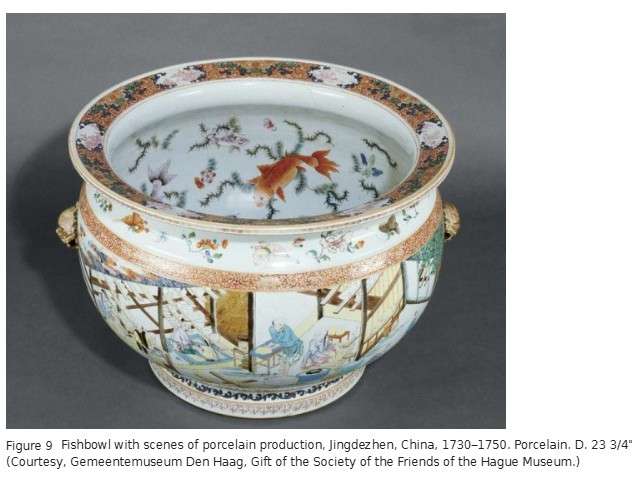

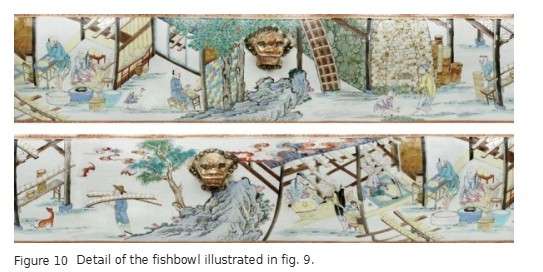

Fishbowl with Scenes of Porcelain Production

This large fishbowl (fig. 9) is one of a small number of pieces of self-referential porcelain illustrated with scenes showing the different steps in porcelain production in Jingdezhen (fig. 10). Probably made for a Chinese or European merchant active in the porcelain trade, it helps explain why Chinese porcelain was such a successful product.

Porcelain was first produced in northern China, but by the tenth century production had shifted south, primarily to Jingdezhen, in Jiangxi province. Ample supplies of raw materials, a large and skilled population, government encouragement, and transportation networks that linked the region to other markets made Jingdezhen the primary center for porcelain production for China and, eventually, for the entire world.

Jingdezhen was described by François Xavier d’Entrecolles as a city of more than one million people, with so many kilns that at night “one thinks that the whole city is on fire, or that it is one large furnace with many vent holes.”[34]

In Jingdezhen, porcelain was mass-produced in a factory setting in which various tasks, such as mining and refining the clay and shaping the objects, were divided among different semi-skilled workers. D’Entrecolles described the process:

[T]he Workman gives it what Wideness and Height he pleases, and parts with it almost as soon as he has taken it in hand....As soon as the Cup is taken from the Wheel it is immediately given to a second Workman, and soon after delivered to a third, who puts it in a Mould, and gives it its proper Figure: a fourth Workman polishes the Cup with a Chisel, especially towards the Edges, and makes it as thin as it is necessary to render it transparent.[35]

He went on to add, with some amazement, that “it is surprising to behold with what Swiftness these Vessels pass thro’ so many Hands, some affirm that a Piece of China-ware, after it is baked, has passed the hands of seventy Workmen.”[36]

Painting was also done in the same assembly-line fashion; d’Entrecolles noted that

the Labour of Painting is divided in the same Laboratory between a great number of workmen: It is the Business of one to make the coloured Circle, which is near the edges of China-ware; another traces the Flowers, which are painted by a third; it belongs to one to make Rivers and Mountains, to another Birds and other Animals.[37]

These techniques of mass production enabled Chinese producers to make vast quantities of uniform, high-quality pieces quickly and affordably. The highly organized industry was also able to adapt relatively easily to create new shapes and designs to satisfy the needs of new markets and new consumer preferences.[38]

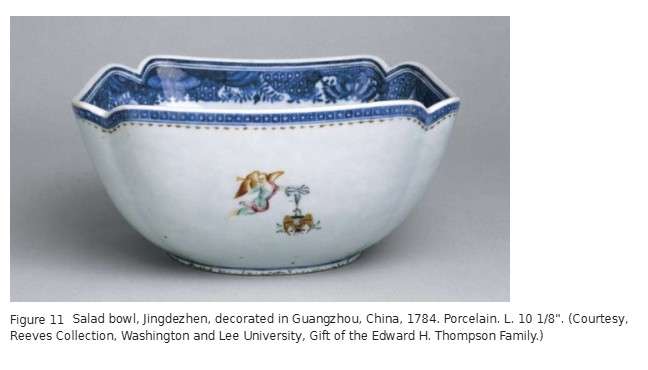

Salad Bowl

It could be argued that the service decorated with the insignia of the Society of the Cincinnati is the most significant group of Chinese export porcelain made for the American market (fig. 11). Commissioned by the first American merchant to go to China, it was owned by George Washington and, later, by Robert E. Lee.

The service consisted of 302 pieces, each of which was decorated with a figure of Fame holding the Society of the Cincinnati badge, which is shaped like an eagle. The society, an organization of Revolutionary War officers that was founded in 1783, is named after Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (ca. 519–430 B.C.), a Roman farmer turned military leader who rescued Rome and then relinquished his power to return to his farm. Cincinnatus was seen by many as the model of a selfless patriot; George Washington, a farmer who had led American troops to victory and then retired to return to Mount Vernon, was seen by many as a modern-day Cincinnatus.

The service was commissioned by Samuel Shaw, a member of the Society of the Cincinnati and the supercargo (an officer on a merchant ship in charge of the cargo) on the Empress of China, the first American ship to trade with China. He recorded the process by which he ordered the service:

There are many painters in Canton, but I was informed that not one of them possess[es] a genius for design. I wished to have something emblematic of the institution of the order of the Cincinnati executed upon a set of porcelain....For this purpose, I procured two separate engravings of the goddess, an elegant figure of a military man, and furnished the painter with a copy of the emblems which I had in my possession. He was allowed to be the most eminent of his profession, but after repeated trials, was unable to combine the figures with the least propriety; though there was not one of them which singly he could not copy with the greatest exactness. I could therefore have my wishes gratified only in part.[39]

His negative comments say more about his own prejudices than the abilities of Chinese painters, but they also point to the difficulties European and American merchants had in communicating their orders to Chinese merchants and craftspeople.

The service was brought to America, and in 1786 Washington’s friend Henry Lee purchased it on his behalf.[40] Reflecting the range of currencies circulating in the new nation, the service’s price was listed at £60, Lee quoted Washington $150, and Washington reimbursed Lee with 32 1/4 guineas’ worth of moidore, a Portuguese coin containing about 4.93 grams of fine gold.[41]

Washington used the service at Mount Vernon and the President’s Mansions in New York and Philadelphia. Conscious that all his actions were carefully watched and that he was creating the model for the office of the presidency, Washington may have used the Cincinnati service to reinforce his identity as a modest, selfless leader in a new, democratic society, who would serve his country without expectation of reward and then relinquish power back to the people.

Following Washington’s death in 1799, the service passed to his wife, Martha, who left it to her grandson, George Washington Parke Custis. Upon his death in 1857, the service passed to his daughter, Mary, and her husband, Robert E. Lee.[42] The Lees shared pieces from the service with family and friends, although, as Mary Lee wrote in the note accompanying the gift of one of the sauce tureens, “they are getting very rare and it is almost like parting with one of the family.”[43]

In May 1861, shortly after Lee resigned from the U.S. Army to fight for the Confederacy, Mary Lee left Arlington, their home across the Potomac from Washington, D.C. She wrote that “the Cincinnati & State China ...was carefully put away & nailed up in boxes in the cellar.”[44] She entrusted the keys to Selina Gray, her enslaved African-American maid. Arlington was occupied by federal troops, and Gray eventually turned the boxes over to the military to assure their protection. They were transferred to the Patent Office and in 1862 were displayed in an exhibit titled “Captured from Arlington.”[45]

The Cincinnati porcelain was almost returned to the Lees in 1869, but Congress refused to surrender articles “so cherished as once the property of the Father of his Country to the rebel general-in-chief.” Ultimately, in 1901, President William McKinley ordered the pieces returned to Custis Lee.[46]

Over the course of the twentieth century, pieces from the service were dispersed to public and private collections. As their prominence rose, so did their price, and in the 1970s the Cincinnati service was even faked, with the eagle and Fame added to pieces of eighteenth-century porcelain.[47]

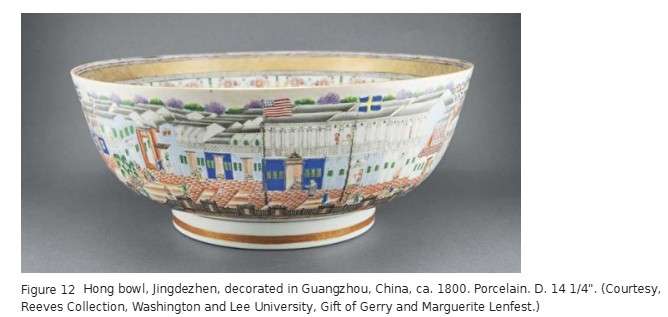

Hong Bowl

China is a vast country, but for much of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries almost all trade between China and the West occurred in Guangzhou, known to Europeans and Americans as Canton. It was through this city that almost all Chinese goods, and almost all information about China, flowed.

Located some eighty miles up the Pearl River in southern China, Canton was one of China’s leading ports. It was convenient to tea-growing regions and production centers such as Jingdezhen. It also had a long history of maritime trade and was used to dealing with foreigners; it had a mosque for Muslim merchants since the mid-ninth century and had dealt with the Portuguese in nearby Macau since the mid-fifteenth century.

Europeans began trading in Canton in the late 1690s, and in 1757 the Qianlong emperor closed all Chinese ports but Canton to Western merchants. This allowed the Chinese government to balance its concerns about the potential threat posed by Europeans (who had often shown themselves to be culturally insensitive, dishonest, and violent in dealings with other Asians) while still encouraging trade and the profits and tax revenue it brought to China. Chinese fears were not unfounded; Canton remained the only city open to foreign merchants until 1842, when Europeans and Americans forced China to open other ports after the Opium Wars.

This punch bowl (fig. 12) depicts the European and American trading offices, or hongs, in the Chinese port of Guangzhou. “Hong” comes from hang, the Cantonese term for company or business, and I-kuang, which translates as “barbarian houses.”[48] Hongs were located along the waterfront outside the city walls and were identified by flags on poles in front of the structures. Few Westerners—all of whom were male, as Western women were not allowed in Canton—were permitted any farther into China. Samuel Shaw, the first American merchant to go to China, noted with some disappointment that “Europeans, after a dozen years’ residence, have not seen more than what the first month presented to view.”[49]

This hong bowl sports the American flag, which would have appeared in Canton in 1784 upon the arrival of the American ship Empress of China. According to Shaw,

Ours being the first American ship that had ever visited China, it was some time before the Chinese could fully comprehend the distinction between Englishmen and us. They styled us the New People, and when, by the map, we conveyed to them an idea of the extent of our country, with its present and increasing population, they were not a little pleased at the prospect of so considerable a market for the productions of their own empire.[50]

First made circa 1765, hongs were painted in a hybrid style by Cantonese painters who combined the traditional conventions of Chinese scroll paintings with Western one-point perspective.[51] Hong bowls were popular among China trade merchants, who bought them as mementos and gifts; Dutch East India Company officials noted in 1780 that hong bowls “must be considered as rarities, which one makes a present of to friends.”[52] John Green, the captain of the Empress of China, must have had the same idea in mind when he bought four.[53]

It probably is not coincidental that the consummate China trade souvenir was a punch bowl. Punch was developed by English China trade merchants in the mid-seventeenth century in Southeast Asia and has a long association with sailors. The term is thought to come from either the Persian word panj or the Hindu word pànch—both of which mean five—referring to the five ingredients of punch: alcohol, water, citrus juice, sugar, and spices.[54]

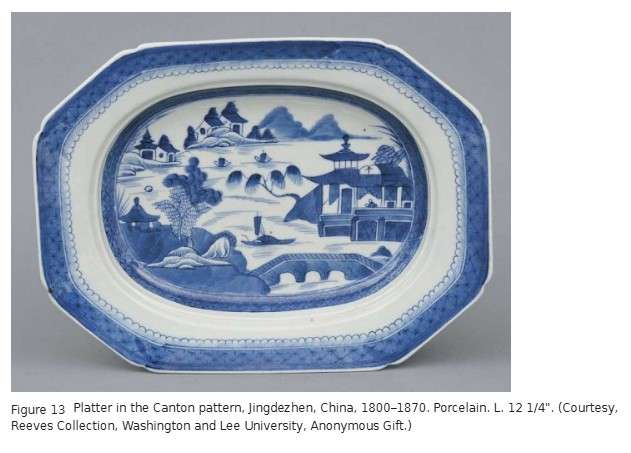

Platter in the Canton Pattern

This platter, decorated in the so-called Canton pattern (fig. 13), belonged to Mary and Robert E. Lee, and is part of a set thought to have been their everyday china while Lee was president of what is now Washington and Lee University from 1865 until 1870.

Named after the port of Canton, the pattern consists of a simple Chinese landscape, with mountains, a meandering river, trees, buildings, and a bridge. The design was inspired by more elaborate Chinese landscapes found on export porcelain from the eighteenth century, themselves inspired by traditional Chinese landscape paintings. Mountains and rivers are key components of almost all Chinese landscape images, and shan shui, the two characters that make up the Chinese word for landscape, evolved from the pictograms for mountains and rivers.

The earliest known reference to the pattern dates to 1797, when “Breakfast setts of Canton, blue and gilt” were for sale for between $2.25 and $3.00 in Canton.[55] Porcelain decorated in the Canton pattern was by far the most popular export porcelain in the nineteenth century. It was moderately priced but still carried some of the cachet of imported Asian luxuries. By 1805 merchants were referring to it as “blue & white of a landscape Pattern & of a good but common kind,” and by the mid-nineteenth century, one merchant reported, with little exaggeration, that it had been “exported in the millions of sets.”[56]

That Chinese porcelain had become the ceramic of choice for consumers looking for inexpensive, serviceable dishes conveys just how much its status had changed by the nineteenth century. Internal unrest, Western imperialism, and increased competition from manufacturers in Europe and the United States meant it was no longer the high-status, high-cost luxury for which China had been known in previous centuries.

Chinese export porcelain, especially with the Canton pattern, continued to be influential, even affecting the way Europeans and Americans thought about China: “Our first ideas of China-dom,” wrote one commentator in 1845, “were formed at meal times, and illustrated with plates.”[57] Chinese export porcelain remained in use in the United States well into the twentieth century. Retailers like A. A. Vantine & Co. in New York could say with confidence that “everybody knows Canton China,” reflecting the enduring appeal of Chinese porcelain.[58]

RONALD W. FUCHS II has been interested in ceramics ever since he was a child collecting sherds from the town beaches on the Chesapeake Bay, where his family vacationed. A graduate of the College of William and Mary and the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture, he has worked at Independence National Historical Park, the Independence Seaport Museum, the New-York Historical Society, Winterthur, and currently is the curator of the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University.

Ron’s work has focused on ceramics since 2000, when he began working with the Leo and Doris Hodroff Collection of Chinese Export Porcelain at Winterthur. He teaches and lectures widely on ceramics and coauthored both Made in China: Export Porcelain from the Leo and Doris Hodroff Collection at Winterthur, with David Sanctuary Howard, and Success to America: English Ceramics for the American Market from the Teitelman Collection, with S. Robert Teitelman and Pat Halfpenny.discovered Japanese prints, challenging the tenets of Western fine art. A trend that was also spreading in the decorative arts, foreshadowing the imminent arrival of Art Nouveau. The first glimmer of the 20th century was on the horizon.

Hand Made and Handheld..Exhibit and Catalog

The catalog of the pieces for the above exhibit can be seen in this catalog. Made available through Arts Of Asia magazine. CLICK HERE TO ORDER

Note: I have already bought this catalog, it is a very good reference on the topic, an essential I think if you are a collector. Best Peter

If You'd Like What We Do

Please consider joining the BIDAMOUNT Community by becoming a PATREON or Global Member Subscriber and help support this site and our YouTube Channel.

Thank you very much. Peter

$5 Per Month

$ 4 Per Month

&

Extra Video's.

Weekly YouTube Video's "AD FREE"

Auction House Report Card

FREE Weekly Copies Of The Antiques Gazette down loadable to your device.

Posts of Interest: News, Events etc.

Downloadable Books and Catalogs. All for $5 a month.

For the extra dollar a Month I think the Patreon Membership gives more bang for the buck.. Both support the YouTube Channel and maintain this site. ..

This Week's Videos

A few items we think are nice.

Live Auctioneers....A few things you might like!

A small sample of things from the Global Member Pages and through PATREON, Join Today on the HOME PAGE

Build YOUR Library: Reference Book Suggestions

For More Reference Books, Visit Our Bookshop. CLICK HERE