Chinese Song to Qing Dynasty Ceramics and Porcelains by Captain Brinkley

Its History Arts and Literature

BY

VOLUME IX

KERAMIC ART

ILLUSTRiITED

ITS HISTORY ARTS AND CHINA

LITERATURE

Chapter I

CHINESE PORCELAIN AND POTTERY

AS TO THE FIRST MANUFACTURE OF

TRUE PORCELAIN IN CHINA

Note this book was part of a series published in 1902 by J.B. Millet & Co. Below is an excerpt from the the original text as well as an enlargeable Flip Book of the entire volume with illustrations. Its a great look back at how Chinese Song to Qing dynasty ceramics and porcelains were viewed in the west over 100 years ago.

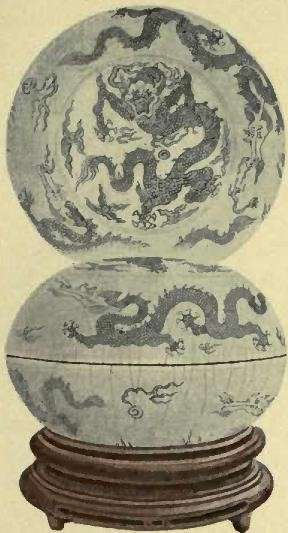

IN former years France stood alone in her appreciation of Chinese keramic productions. By French amateurs only was properly understood the double triumph of estheticism and technique achieved in the monochromatic vases of the Ching-te-chen factories. In England, the popular idea of Chinese porcelain was a highly decorated, formally painted ware. So little valued were monochromatic or even blue-and-white pieces, that if any such found their way to London, they were deemed unsaleable until their surface had received pictorial additions at the hands of Anglo-Saxon potters. Such sacrileges are no longer perpetrated. All Western collectors have now learned to appreciate the incomparable beauty of the Kang-hsi and Chien-lung blues. These fine pieces, as well as their contemporaries of the monochromatic and polychromatic orders, derive additional value from the fact that, so far as human foresight can reach, the potters of the Middle King-dom will never be able to reproduce them with absolute success. To that end this book is an attempt to increase our understanding of Song to Qing dynasty ceramics and porcelains and how they were made.

Those who have read the accounts, recorded in Chinese and Japanese literature, of men almost deified as the discoverers of some new hoccaro clay ; or who have heard the fond tradition how the pate of every choice piece fired at the potteries of the Po-yang Lake had invariably received a century's manipulation ; or how the materials of celebrated glazes were ground and re-ground during the life-time of half a generation until they were reduced to impalpable powder ; or how, to distinguish the true colouring pigment — the Mohammedan blue, worth more than its weight in gold — from the many imperfect compounds which nature's laboratory offered, was an accomplishment possessed by the most gifted experts only ; those who are familiar with all these things have no difficulty in understanding that the decadence of such extraordinary processes, such labours of almost crazy love, was an inevitable outcome of the world's changed conditions. Regarded, therefore, as works of art which have ceased to be produced, and which must become every day more unprocurable, the Hawthorns and other hard-paste blue-and-white specimens which in recent years created a furore among English collectors, were not unworthy of the homage they received. But from a Chinese point of view, such pieces are not to be placed in the very first rank of keramic masterpieces. The instinct of the French amateurs of former years directed them more truly when it inspired their love of monochromatic wares and of soft-paste pieces decorated with blue sous couverte, and  the instinct of American collectors has happily followed in the same direction.

the instinct of American collectors has happily followed in the same direction.

To view the entire book on Song to Qing Dynasty Ceramics and Porcelains

Click below..

It was natural, in view of this appreciative mood of French amateurs, that the first researches into the subject of Chinese keramics should be made by French authors. M. Stanilas Julien led the way with his translation of the Ching-te-chen Tao-lu, or " History of Ching-te-chen Keramics." This work was published in 1856, and has remained since then an authoritative text-book. But M. Julien laboured under a very great disadvantage. He possessed no knowledge of the processes described in the Chinese volume. He was simply a student of languages, competent to render the meaning of an ideograph, but without either the experience of a connoisseur or the education of an artist. Nothing could have been more extravagant than to expect that his interpretation of the Tao-lu would be free from error. The book itself, apart from the special attainments its subject demanded, was not calculated to facilitate a translator's task. Compiled, for the most part, in the early years of the present century, that is to say, when Chinese potters were already beginning to lose their ancient dexterity, its author relied upon tradition for the bulk of his materials ; and, to crown all, died before the volume was completed. The compilation and publication of the information he had collected devolved upon his pupil, Ching Ting-kwei, who, judged by the account he gives of himself, had little knowledge of keramic processes. One valuable work the author of the Tao-lu was able to consult, namely, the Tao-shu, or " Keramic Annals," written nearly half a century previously during the reign of the celebrated Chien-lung. But neither the Tao-shu nor the Tao-lu aimed at furnishing such information as a Western student desires. The object of both alike was mainly to preserve a catalogue of the most celebrated wares with their dates and places of manufacture and occasionally some meagre details of their nature. M. Julien, then, however conscientious as a linguist, could not fail to be misled and to mislead. He was followed, in 1875, by M. Jacquemart, an over-speculative connoisseur, who, great as was the debt of gratitude under which he placed collectors, wrote unfortunately in such a way as to mix the keramics of China, Korea, and Japan in confusion.

Taking some of the choicest specimens of Chinese work, he allotted them to Korea or Japan ; content to assume, in the one case, that Chinese artists never depicted Mandarins on their vases, and that, consequently, all vases thus decorated must be Japanese ; and in the other, that any piece the decoration of which seemed to him to possess both Chinese and Japanese characteristics must come from a country between the two empires, namely, from Korea. Thus wherever Julien had led the public astray, Jacquemart helped to render the aberration permanent. One example is conspicuous : — Julien, falsely rendering a single word, said that the most esteemed variety of the Kuan-yezo (Imperial ware) manufactured under the Sung dynasty (960—I279) was blue. Jacquemart thereupon wrote, " Le decor le plus ancien et le plus estime au Celeste-Empire est celui en camaieu bleu. Il s'execute sur la pate simplement sechee apres le travail du tournage, et crue ; on pose la couverte ensuite, on cuit, et des Tors la peinture devient inattaquable. Dans les temps les plus an-ciens, le cobalt n'etait pas d'une purete irreprochable ; son plus ou moins grand éclat peut donc aider a fixer des dates approximatives. Pour prouver jusqu'a quel point les porcelaines bleaes etaient estimees, it suffit de rappeler qu'on les appelait Kuan-ki, vases des magistrats." Now, the fact is that decoration in blue under the glaze retained all the characteristics of a most rudimentary manufacture throughout the Sung dynasty ; that the colour erroneously translated " blue " by Julien, referred to the glaze itself; not to the decoration, and that the Kuan-ki never included ware having blue designs sous couverte. The whole import of these misconceptions will be presently appreciated by the reader. Their number, and the very false conclusions to which they led Julien, Jacque-mart, and other less notable writers, have contributed to obscure a subject already sufficiently perplexing.

The annals of the Middle Kingdom attribute the infancy of the keramic art either to the reign of Huang-ti, or to that of Shun, semi-mythical sovereigns who are supposed to have flourished some twenty-five centuries before the Christian era. Of these very early wares tradition does not tell anything that can be taken seriously or that need be recorded here. They were doubtless rude, technically defective and inartistic types. At a later date it is stated that Wu Wang, founder of the Chou dynasty (12th century B.C. ), appointed a descendant of the Emperor Shun to be director of pottery, and in a record of the same dynasty the processes of fashioning on the wheel and moulding are described. The pieces produced appear to have been funeral urns, libation jars, altar dishes, cooking utensils, and so forth. The same annals add that these manufactures were earthen vessels, and that they were called pi-ki, or vases of pottery. More than nine hundred years later (B.c. 202), there is talk of another species of ware called tao-ki which differed in some respects from its predecessor, and to which Western interpreters of Chinese history apply the term " porcelain." According to this theory, the manufacture of pottery commenced in China B.c. 2698, and that of porcelain between 202 B.c. and 88 A.D. It is to be observed, however, that among Chinese writers themselves some confusion exists on this subject. Julien reflects their bewilderment.

Of four ideographs each translated " porcelain " by him, the first, tao, is used sometimes generically for all keramic wares, sometimes in the sense of pottery alone ; the second, yao, signifies anything stowed or fired, and has no more specific signification than " ware ; " the third, ki, simply means utensil, and is applicable to stone, iron or pottery ; and the fourth, tsu, is written in two ways, the latter of which, according to some scholars (whose dictum is open to much doubt), was originally employed to designate porcelain proper, though both subsequently came to be used in that sense. When the fact is recalled that even among Western authors it is a common habit to employ the word " porcelain " in reference to baked and glazed vessels, whether translucid or opaque, there is no difficulty in supposing that Chinese writers were at least equally inaccurate. As for M. Julien's nomenclature, the impossibility of relying implicitly on its evidence is shown by the fact that, speaking of a so-called " porcelain " manufactured by the elder of two brothers (Chang), who flourished under the Sung dynasty (960-1277), he says that it was made of " une argile brune " ; that a variety of the Chien ware (also of the Sung dynasty) which he equally describes as "porcelain," was of "une argile jaune et sablonneuse; " and that in other instances the pate of his so-called " porcelain " was of an iron-red colour. Plainly the term " porcelain " cannot properly be applied to such wares, and it becomes evident that both in the original of the distinguished sinologue's translation and in the translation itself, the same looseness of phraseology occurs.

Turning now for information to the neighbouring empire of Japan, it appears that in the middle of the fifth century of the Christian era, a Japanese Emperor, Yuriaku, issued a sumptuary decree  requiring that a class of ware called seiki should be substituted for the earthen utensils hitherto employed at the Court. Ancient Japanese commentators interpret this seiki as another expression for tao-ki, the so-called " porcelain " of China. Now it is known that, despite the importation of Chinese wares into Japan which had taken place either directly or through Korea from the earliest times, and despite the tolerably regular trade carried on by Chinese merchants with the neighbouring empire, not so much as one piece of ware to which the term " porcelain " could be accurately applied, reached Japan before the twelfth century. The seiki of Yuriaku's time cannot, therefore, have been anything better than glazed pottery, and the same is doubtless true of its synonym, the tao-ki, said to have been invented in China at the beginning of the Christian era. In addition to this negative evidence, there are the positive statements of Japanese antiquarians, who unhesitatingly ascribe the invention of porcelain proper to the keramists of the Sung dynasty (960-1279). It was then, they aver,—whatever value the assertion may have — that the ideograph tsu was first written in such a way as to indicate the presence of kaolin in the ware ; and it was then that Japan began to receive from China specimens of coarse porcelain, some of which are still preserved and venerated by collectors.

requiring that a class of ware called seiki should be substituted for the earthen utensils hitherto employed at the Court. Ancient Japanese commentators interpret this seiki as another expression for tao-ki, the so-called " porcelain " of China. Now it is known that, despite the importation of Chinese wares into Japan which had taken place either directly or through Korea from the earliest times, and despite the tolerably regular trade carried on by Chinese merchants with the neighbouring empire, not so much as one piece of ware to which the term " porcelain " could be accurately applied, reached Japan before the twelfth century. The seiki of Yuriaku's time cannot, therefore, have been anything better than glazed pottery, and the same is doubtless true of its synonym, the tao-ki, said to have been invented in China at the beginning of the Christian era. In addition to this negative evidence, there are the positive statements of Japanese antiquarians, who unhesitatingly ascribe the invention of porcelain proper to the keramists of the Sung dynasty (960-1279). It was then, they aver,—whatever value the assertion may have — that the ideograph tsu was first written in such a way as to indicate the presence of kaolin in the ware ; and it was then that Japan began to receive from China specimens of coarse porcelain, some of which are still preserved and venerated by collectors.

That the manufacture of translucid porcelain in China should have preceded its manufacture in Europe by only seven centuries, instead of seventeen as has hitherto been maintained, will not be readily admitted. Yet there is much to support the Japanese view. It is known that before and after the time to which the invention of porcelain is commonly attributed, the Chinese were in commercial communication with the eastern countries of the Roman Empire, and that they received from thence various kinds of glass which they ranked with the seven Buddhist gems. For this glass — of which there were two principal classes, lu-li or opaque glass, and po-li or transparent — they paid immense prices. They had no suspicion that it was artificial, regarding it rather as ice a thousand years old, a precious stone second only to jade. By the Japanese, also, it was held in scarcely less esteem. Beads, probably made on the coast near Sidon, were treasured by Japanese Emperors, buried in their tombs, or preserved among their relics. The Chinese supplied the Japanese with glass, and were themselves supplied by the Syrians, but all the while no Chinese porcelain found its way either to Rome or Japan. Its invention was still in the lap of a distant future. Dr. Hirth, in his recently published work, " China and the Roman Orient," says : — " During the Ta-ts'in period (i.e. the period of China's commercial intercourse with the Roman Orient), " that peculiar fancy for objets de vertu which in Chinese life have at all times taken the place of other luxuries, was not yet absorbed by the porcelain industry, which probably did not begin to assume large dimensions previous to the Tang dynasty. Clumsy copper censers and other sacrificial implements, imitating the then archaic style of the Chan dynasty, monopolised the attention of the rich, together with the so-called precious materials. A large portion of the latter came from Ta-ts'in, and glass is in all the older records mentioned among them." Had Dr. Hirth written " keramic," instead of " porcelain," industry, there would have been nothing to question in this opinion. The Chinese do not seem to have turned their attention seriously to keramics until, as in Japan four centuries later, the growing popularity of tea, under the Tang dynasty (618-907), provided a new function for vessels of faience. Glass was then comparatively out of fashion. Its composition had become known to the Chinese about 430 A.D., and they already excelled in its manufacture. Thenceforth glazed pottery or fine stone-ware became the national taste, until, in the tenth or eleventh century, porcelain was discovered.

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement

account it. Look advanced to far added agreeable from you! However, how

can we communicate?