Bidamount News February 20, 2026, Vol 620

Share this post:

The History of Chinoiseries in France

At the dawn of the French Revolution, the chinoiseries décor trend, already quite battered by the neoclassicism of the Louis XVI style, was on the verge of vanishing completely with the last glimmers of lavish 18th-century pomp. Chinese-style ornamentation was the hallmark of a bygone era, a period of splendor and nonchalance come to be seen as decadent, with chinoiseries considered vulgar, ostentatious, and passé. Fashions now called for an imitation of Greek and Roman antiquity, viewed as the epitome of republican virtue. The Directoire style advocated simplicity and sobriety. Moreover, the disappearance of the trade guilds (corporations) with the strict rules imposed by the Ancien Régime, coupled with the flight of the aristocrats, shook the luxury market and the importation of oriental objects. International trade was disrupted with the start of the wars of the Republic, then of the Directoire, the Consulat, and the Empire, with the United Kingdom controlling the seas, leaving France at a disadvantage. French ornamental language was fueled by the wars of the day, a vivid example to be found in an explosion of Egyptomania after Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign and its Battle of the Pyramids.

After the end of the Napoleonic epic and the return of the monarchy, financial resources were meager and the Restoration saw no major stylistic changes other than the continuation of earlier neo-classical styles. It was not until the Second Empire that 18th-century aesthetics came back into fashion, including chinoiseries, with a new passion developing not only for Chinese-style décor, but Asian arts as a whole. The Goncourt brothers, astute observers of their time who nevertheless harbored some nostalgia for French grandeur, became infatuated with Far Eastern art objects and designs. A vogue that was not without ulterior reactionary motives, lauding the now-extinct aristocratic world of the 18th century and the glory days of France as compared to the more mundane existence of bourgeois society. The example came from higher up, as Empress Eugénie became enthralled with Marie-Antoinette, bringing the Louis XVI style back into fashion with its ribbons, garlands, leaves, and, naturally, chinoiseries. Lacquerware also saw a comeback, as the Empress recovered the furniture of the departed queen for her living quarters in the imperial couple’s various places of residence: Saint-Cloud, Compiègne, Les Tuileries, and Fontainebleau. At Les Tuileries, Eugénie ordered the installation of the ebony-and-Japanese-lacquer writing table made by Adam Weisweiler for Marie-Antoinette, along with other 18th-century creations incorporating lacquers by Riesener and Carlin.

In the Compiègne and Fontainebleau châteaux, the Empress ordered construction of a tea room and a Chinese museum, respectively. She chose 18th-century furnishings for the first, including furniture in red Chinese lacquer, as well as articles in the style of the day. A tasteful mix of influences demonstrating an eclecticism in interior décor that would remain the hallmark of the Second Empire style. For Fontainebleau, the Empress showed even more exuberant orientalism with the installation not only of a Chinese museum in 1863, but a salon des lacques, as well. The gifts from the Siam ambassador, who was hosted by the Emperor two years earlier at the same château, served as the collection’s foundation. It would soon expand thanks to many new objects from China, where the Second Opium War and the Franco-English troops’ ransacking of the (Old) Summer Palace added momentum to global demand for Far Eastern antiquities.

From his place of exile in Guernsey, Victor Hugo protested this destructive looting. The great writer, a collector of many Far Eastern art objects himself, a man who even took to drawing panels imitating Asian lacquers to decorate his bedroom, much admired Chinese civilization. He denounced the plundering of the Summer Palace, comparing France and England to “two robbers” and enthusiastically praising the destroyed monument: “Imagine some inexpressible construction, something like a lunar building, and you will have the Summer Palace. Build a dream with marble, jade, bronze and porcelain, frame it with cedar wood, cover it with precious stones, drape it with silk, make it here a sanctuary, there a harem, elsewhere a citadel, put gods there, and monsters, varnish it, enamel it, gild it, paint it, have architects who are poets build the thousand and one dreams of the thousand and one nights, add gardens, pools, gushing water and foam, swans, ibis, peacocks, suppose in a word a sort of dazzling cavern of human fantasy with the face of a temple and palace, such was this building.”

And such was the paradox of this second chinoiseries wave. While it began as an imitation of the 18th century, its relationship to Asian reality was quite different. While the Europeans of yesteryear fantasized about the Far East by obtaining or admiring fascinating and exotic objects, the Western world was now in direct contact with several of that region’s countries, leading wars to force them to open to international trade, an early attempt at globalization, but at bayonet-point, resulting in the looting and despoilment of precious cultural structures and objects. The East was no longer some far-off land onto which Westerners projected their fantasies: It was a place of clearly identified countries, customers, allies, or enemies.

In the second half of the 19th century, the greatest vogue for Asian aesthetics focused on Japan, which had been forcibly opened to foreigners in 1853 by the United States. In Paris, the Empire’s participation in the International Exposition of 1867 triggered a fashion frenzy for Japonism, paving the way for more than 150 years of French fascination for this archipelago across the world. This was the first time that the country presented a pavilion at the fair and the crowds of visitors were awestruck by its artworks, spreading the craving for Japanese products beyond what had, up until then, been only a limited circle of interested elites. Since industrial techniques had evolved in the interim, workshops could now produce lacquered objects on a larger scale, using techniques such a papier maché. In 1879, the Musée Guimet opened in Lyon, presenting the Asian art collections of French industrialist, traveler, and connoisseur Émile Guimet. The building would be moved to Paris a few years later.

Two years later, in his book La Maison d’un Artiste, Edmond de Goncourt described his house, furnishings, and collections. Here is Maupassant’s review of the work published in the Le Gaulois newspaper: “And no house, in fact, is more curious to visit than his. It is a résumé of 18th-century French art and, simultaneously, a cursory tableau of the wonders of the East, a visual recounting of these sparkling industries of China and Japan. Because Goncourt, more than any other, was born possessed by a passion for knickknacks. This is obviously his vice, that beloved, ruinous, gnawing vice that everyone carries within himself.” Further on in the text, the writer continues: “But we enter the sanctuary, the collections room. Here, China and Japan dominate. All around the apartment, large display cases enclose treasures. Porcelains, in fact, a plate depicting a bird perched on a branch is the most perfect I have ever seen.”

The end of the 19th century saw the taste for Asian aesthetics in art becoming more widespread by virtue of Japonism, which found particularly fertile ground in painting. The young Impressionist guard discovered Japanese prints, challenging the tenets of Western fine art. A trend that was also spreading in the decorative arts, foreshadowing the imminent arrival of Art Nouveau. The first glimmer of the 20th century was on the horizon.

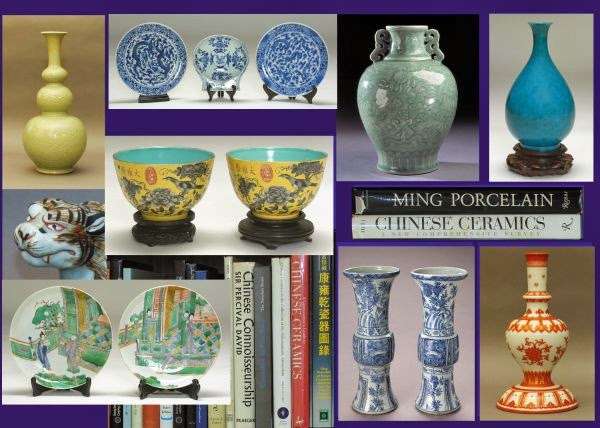

Hand Made and Handheld..Exhibit and Catalog

The catalog of the pieces for the above exhibit can be seen in this catalog. Made available through Arts Of Asia magazine. CLICK HERE TO ORDER

Note: I have already bought this catalog, it is a very good reference on the topic, an essential I think if you are a collector. Best Peter

If You'd Like What We Do

Please consider joining the BIDAMOUNT Community by becoming a PATREON or Global Member Subscriber and help support this site and our YouTube Channel.

Thank you very much. Peter

$5 Per Month

$ 4 Per Month

&

Extra Video's.

Weekly YouTube Video's "AD FREE"

Auction House Report Card

FREE Weekly Copies Of The Antiques Gazette down loadable to your device.

Posts of Interest: News, Events etc.

Downloadable Books and Catalogs. All for $5 a month.

For the extra dollar a Month I think the Patreon Membership gives more bang for the buck.. Both support the YouTube Channel and maintain this site. ..

This Week's Videos

A few items we think are nice.

Live Auctioneers....A few things you might like!

A small sample of things from the Global Member Pages and through PATREON, Join Today on the HOME PAGE

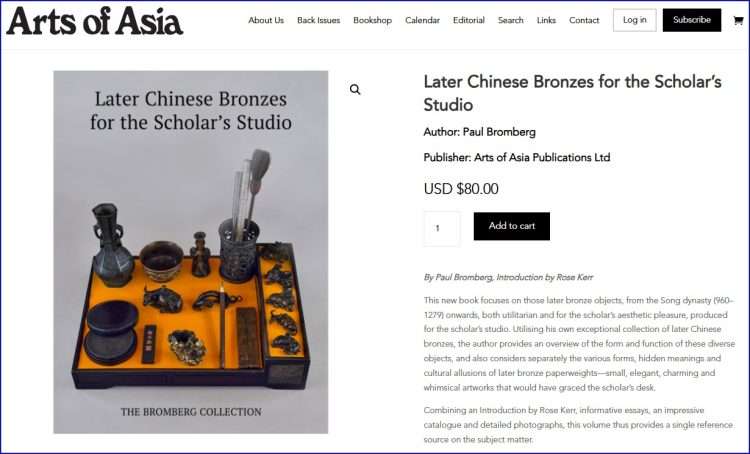

Build YOUR Library: Reference Book Suggestions

For More Reference Books, Visit Our Bookshop. CLICK HERE