Qianjiang Style of Chinese Porcelain

An introduction to Qianjiang Style of Chinese Porcelain; I have often fantasized that the evolution of artistic style in the history of art in the world, particularly in painting, can be hung on a single, central thread. A thread that runs from Neolithic graffiti of hunting scenes to the Maestà of Duccio painted on wood in the XIII century, to the paintings of the Renaissance, to Yuan paintings on paper, paintings on silk, to Islamic pottery, and to the amazing decorations found in Chinese art including the Qianjiang style of Chinese porcelain.

Both the Orient and the West gave birth to, evolved, interconnected, and incorporated the nearly common expressive language we have arrived at today.

But there are different conceptual and artistic premises that separate the Orient—Middle and Far— and the West, however, that are encapsulated in three areas: objectivity, spirituality and subjectivity.

Fig 1 Greek statue; Laocoonte; ca. I century B.C – I century A.D.; source: www.tuttartpitturasculturapoesiamusica.com

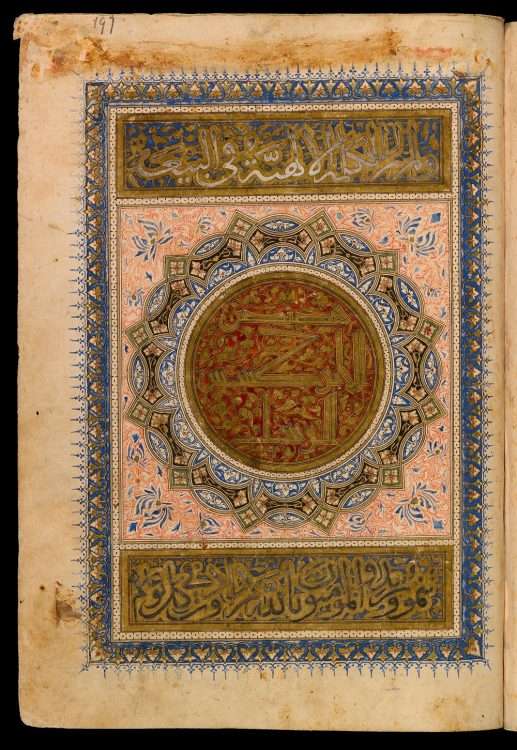

In the West, the evolution of research into perfect beauty is embodied by the representation of an “objective beautiful” in the exterior world [fig. 1]. In Arabic script, the search for perfection resulted in the theory of the impossibility of reproducing the perfect creation of Allah [fig.2]. The sinuous curved lines of Chinese decorations, simple drawings enhanced by further brush strokes, illustrate the strength and the interior energy of everything that animates “matter” and that shows itself in the light of subjective beauty, perpetual motion, and the pulse of the exterior world [fig.3]. These pre-conditions can be considered the main key points that conceptually affected—at least in recent times— the evolution of art in the Orient and the West.

Between the end of the XIX century and the beginning of the XX century, moreover, Europe conceived an interest in researching the stylistic beauty of common pieces of furniture. Bauhaus [fig.4] extended this concept to products of daily use—“beauty for everyone,” —that has culminated in design as art that stands on its own.

[fig. 5].

Fig 2 Part of the New Testament in Arabic; scribe: Thuma al-Safi Yuhanna, Damascus; 1342; source: www.bl.uk

Fig 3 A Chenghua mark and period (1464 – 1487) blue and white cup in porcelain; source: www.alaintruong.com

Early Chinese Bronzes

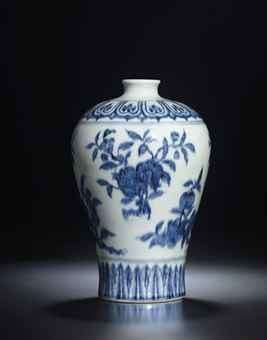

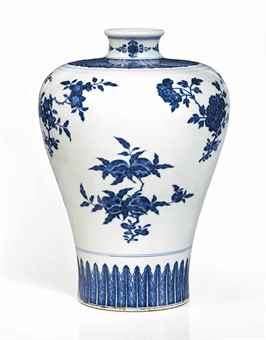

In China, this concept of objects as art was present from very early on. The all important shape of the object comes first and drives the initial impression. The interest in the reproducing the extraordinary bronzes of Shang Dynasty in porcelain (ca. 1600 B.C. – ca. 1046 B.C.) [fig.6; 6.1], the obsessive refinement of monochromes from the Song Dynasty (960 A.D. – 1279 A.D.) [fig. 7], the evolution of shapes during the dynasties [fig. 8; 8.1; 8.2] culminated in molded objects having life of their own. Shaped with soft lines that give off a sense of movement and seem to emanate a heavenly light—one that appears to transmigrate to earthly reality—the vessels were often compared to unworldly, eternal, mythical, immaculate, and ideal figures. These qualities came centuries ahead of the Design concept of our modern era.

-

Fig 6.1. A yellow-glazed tripod censer (Ding) Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644); VII / VII century; source: elogedelarte.canalblog.com

Fig 8.1. Ming Dynasty blue and white Meiping vase; Yongle period (1403-1425); Peaches; source: Christie’s

8.2. Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912) blue and white Meiping vase; Qianlong mark and period (1736-1795); Peaches and flowers; source: Christie’s

Finding the Origins of the Qianjiang Style of Chinese Porcelain

In my opinion,

Qianjiang Chinese porcelains represent the encounter, whether conscious or not, and artistic synthesis of painting, calligraphy, poetry, and the shape of an object.

Qianjiang literally means pale umber. It derives from a literati style of painting on paper created during the Yuan Dynasty (1279 A.D. – 1368 A.D.) in China.

The word Qianjiang was used to describe the painting style of landscapes by the Great Master Huang Gongwang (Changzhou, Jiansu, 1269 – 1354), one of the “Four Masters” of the Yuan Dynasty (Huang Gongwang, Wu Zhen, Ni Zan, Wang Meng) [fig. 9; 9.1; 9.2; 9.3].

The paintings were a combination of inscriptions and landscapes defined by ink outline and completed with brush strokes of pale umber that emphasized the well-lighted areas [fig. 10].

Fig 10 Huang Gongwang: Search for the Tao; Hanging scroll, ink and colors on paper, 101.3 x 43.8 cm, Palace Museum, Beijing

Qianjiang Style of Chinese Painting

Different tones of ink were applied for outlines, rocks, the shady areas of the mountains, and for the trunks of trees. The colors used to achieve these particular color schemes utilized a pale red-brownish color (pale umber, indeed) for leaves, water and illuminated parts.

The term Qianjiang with regards to porcelain refers to a style born at the end of the XIX century, during the reign of the emperor Tongzhi (1861 – 1875). The style quickly declined around 1911, near the beginning of the Republic of China (1912 – 1949). This style of decoration on porcelain is closely related to Huang Gongwang’s landscape paintings on paper and silk.

Qianjiang enamels glazes and colors

Qianjiang enamels were directly applied to the porcelain glaze, giving the impression of a watercolor painting on paper or silk. The chief visual difference with Yuan paintings is that since they were painted on objects and not on paper, the perception of the scene on porcelain is "uninterrupted"—when you turn the object the painting unrolls, creating a panorama in three hundred sixty degrees similar to what happens when you rotate a globe. Furthermore, the scene is inevitably shinier since it is painted on glazed porcelain instead of paper.

These soft to light colorations give each piece a gentle atmosphere when combined with the delicate and warm earthy color. Pieces were fired at low temperatures and utilized colors made by the artists themselves. They combined individual pigments to create enamels that best expressed the effect and atmosphere desired.

The first scenes painted on porcelain in Qianjiang style were landscapes, recalling exactly the traditional paintings on paper of the Yuan Dynasty masters. At first, the color schemes were directly copied from the traditional style. Then, as the style became popular, more painters accepted the idea of relinquishing traditional landscapes on porcelain in order to satisfy the different and particular aesthetic requirements of a new and expanded clientele. As the demand for Qianjiang products grew to include the merchant class, the style slowly evolved and changed to satisfy more popular tastes. Tones became less pale and more marked, new color palettes were introduced—aquamarine, moss-green, pale blue, violet, light orange and a soft pink— to fulfill the demands of a new clientele that preferred more intense and bright colors. Even the decorations themselves were partly transformed—human figures (Shanghai influence), antiques and birds and flowers were incorporated into the traditional landscapes that were still in pale and suffused colors fabricated by the artists themselves and always accompanied by inscriptions [fig. 11; 11.1]

Fig 11 A little box for ink in Qianjiang style, a written example; Landscape; source: english.cguardian.com

11.1 (Twenty eight Qianjiang plaques unwritten: Landscapes, figures, birds and flowers; source: Sotheby’s)

Qianjiang taste

Probably the first recipients of these objects were members of the literati class who were distinguished by their highly polished and advanced tastes. As a result, the production volume during the first period of Qianjiang style on porcelain in the Tongzhi reign and in the first decade of the reign of Guangxu (1875 – 1908, was very low. In fact, very few pieces were produced for a tight circle of people. Pursuant to collectors and experts of Qianjiang, it is very difficult to find pieces dated before 1885. This period of low production volumes directly correlates with the period before Qianjiang porcelains appealed to more popular tastes.

Even in the West, interest in this kind of Chinese porcelain was negligible until the latter half of the past century. This fact is evidenced by the virtual lack of Qianjiang porcelain in the biggest international auction house sales as compared with Fencai pieces. In Italy, even today this style is still virtually unrecognized.

Changes in the Qianjiang-style

On the timeline of the Qianjiang style on porcelain, there are two dates that are the bedrocks of that trend and the main points of evolution and regression of the style.

As noted above, before approximately 1885, a limited number of pieces were produced for a few people of the intellectual class, and the style and color schemes were still directly tied to the traditional paintings on paper from the Yuan Dynasty.

After this period, and as the popularity of the Qianjiang style began to rise, additional colors and decorative variations were introduced, but for the most part, the essential elements of the style did not stray far from traditional decorations. In particular, artists continued to use light, pale colors as a means to simulate watercolors. After 1894, the style reached its peak of popularity. The enamels became more vibrant yet the style still retained the qualities of traditional Chinese watercolors. The primary reason for the introduction of more vibrant colors was that this pictorial style also appealed to both merchants and working class people. Hence, even things of everyday usage and of low quality were decorated in Qianjiang style. In my opinion, this was the essential contribution and most important innovation of the Qianjiang style—the application of a literati style of painting on medium quality porcelain converted objects of ordinary handicraft into extraordinary artworks.

The more recent porcelains characterized by more vibrant and additional colors—stronger, and with more tonal variations—are often excluded from the Qianjiang style by purists and enthusiasts. Sometimes, decorations with more intense and vibrant colors or ones that represent nontraditional subjects such as birds, flowers or Peku decoration, are not included within the confines of the Qianjiang style, but are attributed—in my opinion, imprecisely—to the Fencai style [fig. 12; 12.1; 13].

Fig 11 A Fencai example: Yongzheng mark and period (1723 – 1725) dish; Peaches and bats; source: Christie’s

12.1.A Fencai example from the Republic period (1912-1949) approximately 1930; Figures; source: Christie’s)

The differences between Qianjiang and Fencai however are clear:

The main distinction, in my opinion, is that in almost all cases, Qianjiang wares are signed and dated by the artist and often the place where the piece was realized is even indicated. Fencai porcelains are not signed—apart from some rare examples that were produced prior to the 19th century and other pieces produced during the Republic period that were signed and dated by the artist. These examples were most certainly influenced by the Qianjiang style, and, in my view, can be seen in some ways as a derivation of the Qianjiang style in the Fencai style [fig. 14]).

Fig 14 Brushpot in Fencai style of the Republic period; Landscapes, figures, inscription; 1928 dated and of the period; Wang Yeting marked; source: Christie’s

A Qianjiang piece is more “creative” than a Fencai one. It is the product of the talents of one or more artists, whereas the latter style is based more on a systematic division of the work that anonymized and alienated the creative process. The Fencai style followed the millenary tradition of repeatedly representing and copying traditional, and even "stereotyped" decorations, over and over again throughout a succession of reigns and dynasties. In other words, the created object was more important than the creative subject.

Another difference is that while both styles use black ink to delimit outlines, the manner of application was different. In the Fencai style, the ink was applied on the glaze and then covered with a transparent, lead-based substance that adhered to the enamel after firing. In the Qianjiang style, the black was mixed with cobalt and applied directly to the surface. As a result, in Fencai the output of black ink is more shiny and bright while in Qianjiang style it is more pallid and opaque.

Furthermore, in Fencai, an opaque substance with an arsenic-based white pigment was applied first to the surface of the piece to fill in the outlines of the areas that would be covered over in color. With the application of different layers of colored enamel, the decorations had a three-dimensional or relief effect, as though they were sticking out from the piece. Additionally, the vividness or dullness of the colors was determined by how much they had been mixed with this arsenic-based white pigment. Conversely, in order to reproduce the watercolor effect, the colors were directly applied onto glazed porcelain in the Qianjiang style and for that reason, the enamels are thinner, with almost no shades of color. When you pass your hand over these pieces, the enamels have a lighter and rougher consistency that is almost dusty to the touch.

Even the latest examples of Qianjiang pieces that employ color and decorative variations are signed and despite the addition of different colors, they still maintain the characteristic soft, pale tones and watercolor aspect that distinguish Qianjiang works from other styles. For these reasons, even the latest works produced prior to the beginning of the Republic period can be considered Qianjiang despite deviations from the original color schemes and decorations.

There are three pioneers and Great Masters of the Qianjiang style on porcelain.

- Chen Men [fig. 15; 15.1], reputedly the inventor of this method on porcelain in the late 19thcentury.

- Jin Pinqing [fig. 16; 16.1]

- Wang Shaowei [fig. 17; 17.1]

The latter two artists worked in the Imperial Kilns during the reign of Tongzhi and exemplified the the exquisite techniques of the early artists in the genre that were prized by China's elite class. These three artists are considered absolutely the best qualitative artists of Qianjiang painting on porcelain.

Fig 16 Jin Pinqing: Landscape, painting on plaque; source: New York art network, www.artinyc.com, Zeng Meifang

As time went by, the the genre evolved and more and more artists took up painting in the Qianjiang The most famous and well-known later masters are Ren Huanzhang [fig. 18], Yu Ziming [fig. 19], and Wang Fan [fig. 20].

Wang Youtang [fig. 21], Xu Pinheng [fig. 22], and Yiuchun [fig. 23] were three popular artists during the second half of the Qianjiang period (1894). Moreover Xu Pinheng worked at the Imperial kilns during the reign of Guangxu.

Fig 22 Xu Pinheng: Undred Peku treasure decoration, painting on vase; source: www.eleganceauction.com

The origin of Qianjiang porcelains was most likely linked to the social and economic environment of its historical era.

During the Taiping revolution (1851 – 1864), rebels assaulted and seized the Imperial kilns and almost all the lots were destroyed. The majority of pieces that escaped destruction were shipped outside of China, and this only added to the shortage of new products in the domestic market. This event, combined with the high production costs of Fencai and blue and white porcelains, greatly increased the demand for low cost, lower quality objects from an already poor population further upset by war.

It has been theorized that Cheng Men tested the Qianjiang style on porcelain as a means to reduce production costs because it is both technically easier and faster than the Fencai and blue and white methods. As production costs went down, quantities went up, and sales volume increased as a result.

All of these factors were intricately linked together. Faster production times, reduced costs and a new style of painting on porcelain piqued the interest of new artists as well as merchants ready to enter the porcelain market to profit from the new tastes of a socially and culturally evolving population. As a result, many new, private kilns were established for the production of Qianjiang pieces.

Due to simple economics, these private kilns were far less likely than the Imperial kilns to use high quality raw materials or high firing temperatures. As a result, medium quality enamels, low firing temperatures, and poor quality porcelain have all contributed to a more rapid material degradation Qianjiang pieces as time goes by—most of the pieces are quite worn out and parts of the decoration, inscriptions included, have been erased or are very blurred (if put against the light, many have the “ghost” of a decoration pr inscription on the glaze). And oddly enough, the same factors that contributed to the rapid rise of the Qianjiang style—a social, economic, and political climate that increased demand for cheaper, lower quality porcelains—were the main factors that contributed to the rapid demise of the Qianjiang style.

Another unique feature of Qianjiang style porcelain is that it represents a very clear demarcation between traditional and modern techniques and materials.

After 1911, oxide-based, silicate, synthetic pigments were imported from Europe and Japan into China. While these enamels do give a watercolor-like impression, the range of colors and different tonal variations is far greater and most of the colors are not made by hand but by directly mixing existing colors. Even if the visual effect is very similar these new pieces are not Qianjiang because these newer enamels are less opaque, shinier, and “watery”. The new style born after 1911 is called Shuicai [fig.24].

In essence, the primary contribution of the Qianjiang style to the art of Chinese porcelain was the diffusion of "elite" tastes to a broader social strata because it introduced painting on objects of a lesser quality and craftsmanship than Imperial examples or pieces created for the wealthy literati class.

For the first time, pieces destined to be painted and signed weren’t only screens, plaques, tiles, vases, and scholarly wares intended for exhibition but also included more humble objects such as ordinary teapots, bowls for washing hair, hat stands, tea services, wine services, dishes, and objects for daily crafted from medium to low quality materials.

While certain, more important Qianjiang wares were still produced for show, the Qianjiang style also gave utilitarian objects a certain artistic completeness and autonomy, distinguishing them from traditional objects of daily use. In fact, they’re almost always signed, dated and often marked, and, in my opinion, this may be their most significant innovation.

Another peculiarity of Qianjiang wares that appears quite frequently is the use of “orange-peel” porcelain that accentuates the visual effect of a watercolor.

In addition to paler colors along with a subtle pigmentation of colors (all handmade by the artist himself) and the luminous, evanescent style of painting that resembled watercolor on paper, inscriptions are another very typical hallmark of Qianjiang porcelain. These inscriptions were almost always in cursive and included the signature of the artist, the date and place where the object was realized, a poem or little story, and the mark on the base.

Often, artists wrote poems in their own handwriting that incorporated the concept of the distilled, artistic lightness of Chinese culture where the goal of visual artists was to use lines and curves to represent the vital energy of matter. The sense of these short, literary works was synchronized with the flowing style of drawing and the evanescence of the painting style of the decorations. The date, the place and the artist's signature are also integral and essential elements of each piece—even if they are not present as a unit. As said before, from my point of view, these elements gave the products a greater autonomy, or independent character, as works of art. They were conceptually complete, not part of a trend, a “style,” or a set. They were pieces that had their own life, identity, and objective and as such, began to break down the artistic and conceptual wall between far East and West, between subjectivity and objectivity.

Furthermore, the artists endeavors to achieve perfection in their chosen style of calligraphy also resembles the creative breath that characterized the works of the best calligraphy masters of the Islamic tradition. The inscriptions were painted with more than simply ritualistic script. They were drafted with swift, determined strokes and vibrant lines that transmit the life force and character of the artist himself. High quality Qianjiang porcelains have a great calligraphic quality, instantly recognizable even by those who are not familiar with Chinese characters.

Writing was an essential element of the Qianjiang style and another element of it that marked the emergence of a style of Chinese porcelain that was in the vein of the artistic traditions of different cultures.

The reign marks are another element that distinguish Qianjiang porcelain from the styles that directly preceded and came after it. The most frequently utilized marks are Tongzhi [fig. 25], Guangxu [fig.26], and the Imperial kilns [fig. 27].

It is virtually impossible to find mark and period Tongzhi Qianjiang porcelain. Pieces that have the Tongzhi four or six character mark stamped on the base during the later Guangxu reign are more prevalent on the market.

Fig 25 Example of Tongzhi stamped four characters mark but impressed during the reign of Guangxu and of the period of Guangxu; source: www.chinese-antique-porcelain.com)

Qianjiang Marks

The most common marks are Guangxu along with the apocryphal one of the Imperial kilns.

While various artists worked in the Imperial kilns, the Imperial kiln mark on Qianjiang porcelain was a fabrication. It was during the Guangxu reign that the style became popular and was produced in many private kilns that were in competition with each other. The best quality objects were stamped with the mark of hte Imperial kilns in order to differentiate them and to draw the attention to a more “renowned” artist. This is the reason why many Qianjiang pieces during the Guangxu reign had the apocryphal mark of the Imperial kilns.

Fig 27 An example of the stamped mark of Imperial Kilns; means: Imperial ware made for the interior court; source: www.big5.huaxia.com)

This very fascinating , revolutionary, and innovative style has left an indelible mark on Chinese porcelain despite its short life. Still virtually unknown, it remains almost a "niche market." As mentioned earlier in this article, even famous auction houses rarely have Qianjiang pieces, and if they do, they are pieces created by a small and elite circle of artists. In my opinion, Qianjiang porcelain has been overlooked by the market, both in terms of interest and consequently of value.

Looking at a Qianjiang masterpiece is like getting lost in a warm, water-colored atmosphere that releases and envelopes us in the scent of mystery, wisdom, and lightness. The translucent colors, soft on our eyes, reproduce the sounds of mountains, of the wind, of the rain pelting down on the trees, of running water, in continuous motion and in eternal stasis.

Carlo Santi

Trivigno 12/08/15

Great article Carlo, nice content and images

Many thanks Peter! Thank to you and all your staff tohave given me that opportunity!

Terrific

Thank you Peter really appreciate your comment 🙂

Working?

nice

Thank you Francesca

Thank you,Qianjiang porcelain is area where my knowledge is limited …as far as I understand your article is very educative,..enjoyed reading it

Many thanks Peter I’m happy you appreciate my work! 🙂

Great article, Carlo! It’s very well written, and while I had seen these sorts of plaques that you’ve described, I’d never really given them much thought. You’ve put them in a whole new light. My one question would be, what is the influence of the Shanghai school of painting on these pieces? And is there any overlap of artists?

Thank you Steve nice to hear sweet words from you! Well the Shanghai school influenced the Qianjiang style for the subject painted. From only painting landscape as tradition, overall after 1885 with the “boom” of Qianjiang style on porcelain , appeared changes in decoration, so not only painting landscape but even others subjects as human figures and birds and flowers, that was the Shanghai influence. The reason is that Shanghai has evolved in a different cultural contest more open with foreign trade, so less “tied” to the tradition and with a “different taste”. A lot of artists stationed in Shanghai and that influenced not only their art but Qianjiang in general. 🙂 What do you mean with overlap of artists?

Amazing! Thanks for sharing

Thank you my friend!

A very erudite and extremely well researched study on a short but fecund period of Chinese porcelain production which I knew little or nothing about but which however has made me aware of the very fine landscape painting in the traditional watercolour style that evolved in China at the turn of the 19th century. This style is a discreet swan song that concludes the concatenation of imperial dynasties over at least three centuries. Although I doubt whether I would ever actually collect it myself I am grateful to Carlo for bringing it to our attention

Thank you Kenneth for your kind words, really appreciated! 🙂

Phew I thought we had lost it again

As an introduction to Qianjiang porcelain, this is a very well wriiten work. Its well reasearch, explained and nicely presented. Sincere congraulations.

Thank you Simon, is a honor hear that from you 🙂

Well written introductory article. In China it is now getting difficult to find good qianjiang porcelains. They are treasured by the collectors who rarely resell them. Nowadays there are many fake pieces in the market. The standard of the painting can be rather good and can fool seasoned collectors especially if old porcelain is reused to draw them. The only weakness is the calligraphy which requires years of training in order to write well.

Regards

Nk koh

Thank you Koh Nai King for your comment, your kind words and addictive info you give us! Really appreciate 🙂

Bravo Carlo!

Congratulations, a great study, really well presented and documented.

Thank you for this.

Giovanni

Thank you Giovanni! 🙂

Found your article only today as I started to actively partecipate in Facebook and began browsing about. Well written and documented it is a very good introduction to a subject that merits serious study but has so far been very poorly divulgated in English language. My sincere thanks for publishing it.

Kindest regards.

Diego

Dear Diego,

Thank you very much! 🙂

Dear Diego,

Thank you very much! 🙂