|

From the HAN DYNASTY to the end of the MING illustrated in a series of 192 examples selected, described and with an introduction. To see some of the illustrations scroll down and take a peek.

To have your own version for FREE of THE ART OF THE CHINESE POTTER check the links below, its the FULL book.

FIG. 2. Bulb-bowl, circular, with three cloud-scroll feet ; of shallow bowl-shape with grooved band below the lip outside and a row of studs. Grey porcellanous ware of fine grain with thick opalescent glaze, mottled grey inside with prominent " earth-worm " marks ; on the outside the glaze which runs in thick welts on the lower part is purple streaked and splashed with flocculent grey. The characteristics of the base will be seen on the next plate. With regard to the form, the Po wu yao lan remarks " of these (Chan) wares, the sword-grass bowls and their saucers alone are refined." It would appear that the flower-pots, such as that of Plate XXXV, are the sword-grass bowls, and that shallow bowls like the present one were originally used as saucers or stands for the flower¬pots. They would, and indeed did, also serve separately as bowls for growing bulbs.

Chan ware. Sung dynasty. D. g• 5".

In the possession of Mr. George Eumorfopoulos.

Written by L. HOBSON, and content by L. Hetherington

Keeper of the Department of Ceramics and

Ethnography, British Museum ;

Author of "Chinese Pottery & Porcelain," "The

Wares of the Ming Dynasty," etc., etc.,

____________________________________________

Click the title below for your own FREE PDF Copy of

THE ART OF THE CHINESE POTTER,

and simply save it.

Or you can view online anytime by clicking here: Hobson

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

Below are just a few examples of what you will find in this wonderful old book.

Some image selections and text from,

THE ART OF THE CHINESE POTTER

By. Hobson and L. HETHERINGTON

Author of "The Early Ceramic Wares of China,"

The Art of the Chinese Potter, the original introduction.

Many students and collectors of Chinese pottery and porcelain find greater help from examination of good illustrations of the wares which delight them than they gain from reading detailed descriptions. So far as the later wares of China are concerned, and by that term we mean the examples produced after the close of the Ming dynasty in the middle of the 17th century, several volumes of plates have been produced. But apart from the illustrations accompanying the descriptive accounts of the pre-Ming and Ming wares, there is a dearth of informative reproductions of the work of the earlier potters.PREFACE

The object of this volume is to furnish the collector with a series of representations of some of the finest examples which are known to exist in this country. The description of each specimen has been carefully made so that with the plate before him, the collector may realise as far as possible the main characteristics exhibited by it. Care has been taken to select examples which have not been well illustrated in accessible works, for it is tiresome to be confronted with notable pieces which are already familiar. But this course has involved the exclusion of a number of magnificent specimens which would naturally find a place in this volume. On the other hand, there are fortunately in this country a number of private collections of first-rate importance from which it has been our privilege to draw. To all who have placed their cabinets at our disposal we tender our sincerest thanks ; as the ownership is indicated in each instance it is unnecessary to particularise further the collections used.

The most famous album of fine examples of Chinese porcelain was that compiled by Hsiang Yfian-Oen in the 16th century. He added to the interest of his specimens by describing in many cases the circumstances under which he or his friends acquired them. We have been tempted to do the same, for an account of some of the adventures experienced by our friends in the pursuit and capture of their treasures would be entertaining. But we have refrained from doing so because we might deprive those collectors of some of their best stories, and thereby return evil for good.

By way of introduction a short account is included of the main features which mark the growth of the art of the Chinese potter during the periods concerned, and a brief description is furnished

of some of the famous kilns which were operating at different times in China. Any more detailed account of the wares would be out of place, and for this other works should be consulted. At the same time attention has been paid to certain recent theories which have not as yet received public examination.vi

In a work of this description success mainly depends upon the artistic appreciation and experience of those responsible for the photography and colour guides from which the blocks are produced. We desire to express our thanks to the artists for the care and skill they so unremittingly bestowed upon the task.

June, 1923.

Song Dynasty vase

Vase with ovoid body moulded in ten lobes, tall slender neck with flaring mouth, and low foot cut in a leaf and tongue pattern. On the neck is a carved band of stiff leaves alternately wide and narrow between wheel-made rings : three concentric rings inside the mouth. Porcelain with thick, white bubbly glaze with a faint tinge of blue which is accentuated where the glaze runs thick in the hollows of the form. The base is unglazed for the most part and discloses a biscuit of rather granular type which has burnt a reddish brown : there are the marks of a ring of supports. The form of this beautiful vase was borrowed by the Corean potters for their celadon.

Ju type. Sung dynasty. H. 1o".

In the possession of Mr. H. J. Oppenheim.

Han Dynasty Jar

Wine-jar with depressed globular body, high neck, and slightly expanded mouth : high foot,.slightly spreading, and flat beneath. On the sides are two tiger-masks in applied relief with ring handles (in the style of a bronze) enclosing a pattern of raised dots. Otherwise the plain surface is relieved only by groups of horizontal wheel-made rings on the neck and body. Red pottery with leaf-green glaze encrusted with golden and silvery iridescence due to prolonged burial and consequent decomposition of the glaze. Drops of glaze have formed on the mouth-rim suggesting that it was fired upside down.

Han dynasty. H. 17.5".

In the possession of Mr. 0. C. Raphael

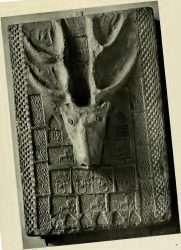

Han Pottery Relief of Stag Head

Ornamental brick of dark grey pottery with a stag's head moulded in high relief, and stamped ornaments consisting of (1) tiger-masks and rings, (2) a palm tree between two buildings, (3) a chariot, and (4) lozenge diaper. Borders of matting pattern. Found in the Kaifeng district, Honan.

Han dynasty. H. 22".

In the British Museum.

Han Dynasty Well Head Pot

Well-jar of buff pottery with green glaze now iridescent from age and burial. The jar is in the form of a well-head with an erection to hold a pulley wheel, sheltered by a penthouse with tiled roof : the ends of the cross-beam are ornamented with two well-modelled dragon heads ; on the rim of the well a bucket is resting.

The tomb furniture of the ancient Chinese included models of all kinds, not only of domestic objects but of farm buildings and implements. Some of these, such as the granary towers and well-heads, lent themselves more readily than others to ornamental representation.

Han dynasty. H. 19.5".

In the possession of Mr. A. L. Hetherington.

This is a landmark book, well illustrated and we thought it would nice to let you have your own copy of The Art of the Chinese Potter For FREE right on your computer.

More Text below...from the book.

There is only one manufactured material which has been identified so closely with a nation in the eyes of the English-speaking races that the name applied to it is that of the country of its origin. China is the name given not only to that vast empire of the East inhabited by the Chinese, but to the product for which that empire is most famous in Western estimation. The children of this country become familiar with the word china as signifying the cup or plate from which they eat long before they learn that there is a country of that name.AN INTRODUCTION

Circular dish with low slanting sides and flat centre, resting on three " cabriole " legs. Soft white pottery with incised designs glazed white and yellow in a blue ground. The glaze is soft looking and, as usual, finely crazed. In the centre is the design of a mirror of " water-chestnut " form enclosing a medallion with a flying crane. Dishes of this form have been found in tombs with a number of small cups set out on them. Tang dynasty. D. 1 I.5". In the possession of Mr. George Eumorfopoulos.

China is the term used popularly to denote pottery, earthenware, and porcelain ; and vessels were made from all these materials by the Chinese in different ages.

But while the Chinese have been regarded as the master potters of the world, and their art has been the inspiration of their fellow-craftsmen elsewhere, it is interesting to note that their skill was obtained comparatively late in the world's history. Egypt, Persia, and Greece were certainly in the field before the Chinese, who derived much of their knowledge, especially in regard to glazes, from contact with the West. The patience and industry for which they are noted soon placed the Chinese ahead of all their rivals, and their supremacy was hardly challenged before the 19th century.

Prior to the 2nd century before the Christian era, the potter's art in China was limited to fashioning vessels of utility in pottery, and it is generally believed that glaze was first employed during the Han dynasty (B.c. 206-221 A.D.). Recently' some criticism of this theory has been put forward, and the counter-suggestion has been made that the introduction of glaze dates from about the 5th or 6th centuries.

This is not an appropriate occasion to enter upon a full discussion of the arguments advanced which in any case are of a negative character. It is sufficient to say that they have not shaken our faith in the Han attribution of the earliest lead-glazed wares. The reference made below to the finds at Samarra of fine porcelain with high-fired felspathic glazes affords definite proof of the existence of wares of this kind as export products in the Tang dynasty. Before examples could have been available for export to Mesopotamia, manufacture on an extensive scale and for a considerable time must have been proceeding in China ; and it is not unreasonable to assume that true porcelain was being made in the early part of the Tang dynasty.THE ART OF THE CHINESE POTTER

By post-dating the earliest examples of lead glazes on pottery bodies to a period shortly before the establishment of the Tang dynasty we would have to accept the idea of a very rapid development of potting technique within a short space of time. It is difficult to believe this to have been possible, having regard to the scientific knowledge possessed in China at that period.

But the Han potter made no very ambitious attempts at artistic productions, although, as we hold, he knew how to glaze his vessels. The pottery was utilitarian, and the specimens with which we are familiar are those made for burial with the dead. It was a custom in China to put into the tomb replicas of vessels and objects used in everyday life for the service of the dead in a better land. Thus we find models of farmyards, granary towers, well-heads, and cooking stoves, as well as jars, ewers, dishes, and cups from which the spirits of the departed might eat and drink. Plate I shows a fine example of a typical Han wine-jar, and Plate III a model of a well-head. The decomposition of the glaze on these wares has given an adventitious beauty to them ; the lead silicate glazes have become iridescent, and a beautiful silvery sheen is generally seen on part or the whole of the object.

Model of a horse in unglazed, soft white pottery. The saddle, saddle-cloth, hoofs, and rosette ornaments on the trappings are covered with unfired red pigment which has flaked off in places. The straps on head, collar, saddle, and girth are shown up with blue pigment, and the rosette orna-ments are picked out with the same colour.

The Bactrian horses of which this is a fine model were first imported into China during the second century before the Christian era, and by the Tang dynasty were the possession of most of the Chinese notables. The Tang tombs of im¬portance usually contain models of these horses and examples are now familiar in this country. But the fine modelling in this instance and the life imparted to the movement of the animal are somewhat exceptional.

Tang dynasty. H. i6".

In the possession of Mr. F. N. Schiller.

The next great epoch in Chinese history was the Tang dynasty (618-906 A.D.), and by this time ceramic art had reached a very high standard of excellence. Further evidence of contact with the West is seen in the models of men and animals made in pottery at that time. The fine figures of Bactrian horses and camels show how these animals had become common objects in China by importation, and many of the human figures indicate types of faces which are certainly not Chinese. Plates X, XIV, and XVII illustrate these facts.

It is natural, too, that Buddhist influence should be seen in many of the figures dating from the Tang dynasty. Introduced into China perhaps as early as the 1st century A.D., Buddhism occupied varying degrees of importance in the life of the people ; different ruling houses adopted attitudes of friendliness or opposition to its tenets, but the religion never took deep root in the life of the people. In later times it became very depraved. But still Buddhism has exercised a decided influence on the ceramic art of the early potters, and evidence of its power is seen in the figures of the Lokapala or Guardians of the Four Quarters found in the grave equipment of Tang notables. Figures of Lohan or apostles of Buddha are to be found dating from the same period, and the great Lohan in the British Museum is a very fine example not only of the magnificent potting of the period but of Buddhistic art. Plates VIII and IX represent further specimens of the figures of this epoch.AN INTRODUCTION

But the Tang potters by no means confined their attention to the production of pottery figures. While the collector will most frequently meet with these, he will find, if he is fortunate, beautiful vases, ewers, bowls, and dishes, all of which show much distinction and many evidences of Western influence. In their execution the potter employed a wide range of technique. Skilful use of slips' of different colours was made, and these were contrasted with the bodies on which they were superimposed. At the same time bold designs, generally of a floral character, were executed by incising the paste with a sharp point.

Simpler effects were created in the wine-jars and vases which owe their beauty to their graceful shapes and to the single coloured glazes washed over them. These glazes—generally soft lead-silicate glazes—are thin in their application and hardly ever continue to the base of the vessel, stopping short of the foot in an uneven line.

It must not, however, be overlooked that although the soft lead-silicate glazes predominate in the Tang wares, high-fired felspathic glazes were also in use. The view has long been held that the Tang potter probably was master of the secret of the manufacture of true porcelain ; but there was no definite proof available until the recent excavations' at Samarra on the Tigris established the fact. This town flourished between 83o-883 A.D., and in its buried remains fragments of Chinese porcelain with high-fired felspathic glazes have been found. The finds included both white glazed specimens and fragments of celadon ware, showing that in the second half of the Tang dynasty the Chinese potter had reached a degree of certainty in his production of true porcelain sufficient to ensure an export trade as far afield as Mesopotamia. The white wares are very similar to the Ting yao and allied wares of the Sung dynasty ; while the celadons are like those known as " Northern Chinese." Plates XXIX and XXX show examples of early white ware possessing characteristics similar to the Samarra fragments with their gummy white glaze.THE ART OF THE CHINESE POTTER

Usually, however, the Pang body is of a white pipe-clay consistency, but is sometimes hard enough to resist the knife.

During the last few years increasing evidence of the maturity of the potter's art in the Tang dynasty has been forthcoming. Though the sensuous appeal of some of the later Sung glazes is lacking, the Tang pottery excels in graceful outlines and nobility of form. There is nothing small about the Tang ceramic art, and as knowledge of this period grows we shall doubtless have greater reason to admire and appreciate it.

Apparently ceramic factories existed up and down the length and breadth of China wherever suitable clay deposits occurred, but our knowledge to date does not permit us to identify the wares made at the few factories which we know to have been operative at the period ; still less can we differentiate the productions of the many minor centres of which history has told us nothing. Thus it is that we have to rest content at present with assigning wares to such an extensive period of time as the 7th to the loth centuries, with no attempt at all at saying whether particular specimens were made in the north, south, east, or west. To the archaeologist this is vexing no doubt, and will have to be remedied by scientific excavation, but to the art lover it is sufficient to see and admire such fine productions, for instance, as those represented on Plates IX, XIX, and XXI. The men who made the objects there depicted had nothing to learn, so far, at all events, as artistic sense is concerned.

In the Sung dynasty (96o-1279 A.D.) further developments were made. Greater refinement of the materials used for the body of the ware became general, and a wide range of glaze colours was

developed. The lead-silicate glazes were abandoned generally in favour of the high-fired felspathic glazes which could be applied

much more thickly ; as a consequence a depth of glaze and a heightened colour effect were achieved. These thick glazes are fairly typical of the Sung period, though we shall have occasion to note one or two instances in which these felspathic glazes are thinly applied. Simple shapes continued to be fashioned as a rule, but the style and technique of the decoration was more ambitious. With few exceptions the glazes of the period are monochrome.AN INTRODUCTION

We have much more knowledge of the factories operating during the Sung period than we have of the Tang centres of production, and a brief account of the principal ones will help to explain the many examples of Sung workmanship displayed in this album.

One of the most striking of the Sung wares is the Chun yao made at Chan Chou in the province of Honan. While the ancient Chinese writers do not speak in high terms of the products of this centre and give them but slight commendation compared with the eulogies showered upon certain other contemporary wares described below, fine specimens command considerable attention to-day and are much sought after by present-day connoisseurs both in the East and the West. The body varies from a hard porcellanous stoneware to a softer and more sandy type ; the two varieties are distinguished by the Chinese by the terms tz'a t'ai (porcelain body) and sha t'ai (sandy body) respectively.

The glaze is thick and felspathic, showing as a rule a bluish tone which is due to opalescence. In the " soft " Chiins, the sha t'ai of the Chinese, the blue is generally more pronounced and the colour is due to copper. In many of the most striking specimens there are one or more splashes of red or purple, and in rarer cases splashes of green or green bordered with red. The red colour is also due to copper, but in a different condition.

The vessels of this factory which are usually met with are bowls, globular vases, or saucers. These were no doubt made for utilitarian purposes. At the date of manufacture this ware was evidently not held in high esteem, and was not adapted to the delicate and dainty forms required by the scholar and art connoisseur.

A more gorgeous glaze achieved by the Chan Chou factories is that generally displayed on bulb-bowls and flower-pots which were probably supplied for Imperial use. The colour varies from a series of greys through deep purples to a crushed strawberry red. Inside the bowls the glaze is either a blue colour or clair de lune. Pieces of this description which belong to the porcellanous stoneware group usually have numerals, I—ro, incised on their bases, apparently to denote their size. The bases of the vessels are generally washed over with brownish green glaze, and on the circumference of the base will be found a circle of spur marks where the vessels rested on clay " spurs " during the firing.THE ART OF THE CHINESE POTTER

A characteristic of this type of Chun ware, to which importance is attached by collectors, is the presence of marks in the glaze which look like shaky V's or Y's ; these are known by the Chinese as " earthworm " marks from their resemblance to the tracks of tiny worms.

Important examples of these different varieties of Chun yao will be seen on Plates XXXIII, XXXV, and XLI, and Plate XXXIV shows the bottom of a bulb-bowl with its potting characteristics.

In the Yuan dynasty and in the Ming dynasty the traditions were continued, though in the latter period the town was called Yu Chou instead of Chun Chou. In the Yuan dynasty a less gorgeous type of glaze appears to have been made, and the wares generally are of a rougher order ; the distinction is sufficiently marked for the term Yuan tell to be applied to the Mongol products. In the Ming dynasty the ware appears to have gone out of fashion, and the number of accredited specimens of that period is limited, according to present knowledge.

Closely allied to the Chun yao is a more refined ware called Kuan yao. Kuan means Imperial or official, and is the term applied to the products of the Imperial factories established first at IC ai-feng Fu in Honan, and later on to those of the Imperially supported kilns at Hang Chou after the transfer of the Sung court to the South. Of this ware the early Chinese writers speak in eulogistic terms, but beyond displaying finer technique both in body and glaze, it presents features very similar to those of the better examples of Chun yao, in fact it is difficult to say where the Chun succession ends and the Kuan family begins. Specimens of what may be ascribed to the Imperial potters of Kai-fel-1g Fu or Hang Chou are illustrated on Plates XXXVII and XXXVIII.

While the Kuan yao may perhaps be regarded as the aristocratic members of the Chun family, there are relatives of less distinguished appearance. We refer to the rather similar kind of ware produced at factories in Kwangtung in the neighbourhood of Canton and that made in the Ming period and later at Yi-hsing, a town not far removed from Shanghai.

Round Canton, glazed stoneware has been made from very early times, but it was probably during the latter part of the Ming dynasty and after that most of the Kwangtung ware which we see was made. The most common type of glaze met with is a dark blue or purple one with white opalescence variegating it, but there are specimens with a greyish colour which approximates fairly closely to some of the Chun effects. The body is a good deal darker in colour, so that no great difficulty should be experienced in detecting these Southern products.AN INTRODUCTION

The Yi-hsing wares are potted on a hard reddish stoneware body and some of the variegated glaze effects are pleasing ; the glaze generally is a soft one which does not bind too well with the body and consequently shows signs of chipping off.

In marked contrast to the gaily coloured Chan wares is the white simplicity of the Ting yao. This ware was made at Ting Chou in the province of Chihli during the early part of the Sung dynasty ; but after the incursions of the Chin Tartars had forced the Sung emperor to retreat south of the Yangtze to set up his capital at Hang Chou, the Ting Chou potters migrated south also and the majority of them appear to have established themselves at or near Ching-te Chen which was later to become the ceramic metropolis of the Empire. But no doubt many of these potters, and those from subsidiary factories employing the same kind of technique, moved to other centres.

In any case, we know of a wide series of wares closely related to the Ting yao proper, but showing differences which point to several centres of origin. The difficulty of distinguishing the ware made in the north at Ting Chou and that produced in the south later was one which puzzled the ancient connoisseur, for we are told that those who can distinguish between the two " have no reason for shame."

The Ting ware consists of a fine white body with an orange or reddish translucency when potted thinly enough to allow light to pass through it. The glaze is a creamy or ivory white. Incised or moulded designs often ornament the plates and bowls which constitute the majority of specimens seen to-day, and the drawing is distinguished by its boldness and its artistic feeling.

The Ting ware is divided into three classes, the white Ting or pai ting, the flour-coloured Ting or fen ting, and the earthy Ting or t`u ting. The first named is the rarest and is the most lustrous in its glaze. The last named is found in a greater variety of shapes, but the quality of its creamy crackled glaze is inferior, and translucency is rarely observed in the body.THE ART OF THE CHINESE POTTER

One of the characteristics which has for centuries been associated with the Ting ware is the presence of " tear drops " in the glaze. These marks are due to local aggregations of the glaze where it has been arrested in its flow over the surface of the vessel. Pieces were often, but not invariably, fired on their mouth-rims which are frequently found bound in copper to hide the unglazed portion.

There are numerous Sung specimens of the Ting type which do not conform with the general features displayed by the Ting yao proper, and with present knowledge it is impossible to classify these more narrowly. Probably there was a number of factories employing similar technique, especially during the latter part of the Sung dynasty, after the main centre at Ting Chou became disorganised. One of the allied classes of white ware has been called Kiangnan Ting, which implies that it was produced at factories in Kiangnan, i.e. in the two provinces of Kiangsu and Anhwei. The features of this type of ware are a creamy glaze and a close crackle. The effect has not inappropriately been likened to pigskin or to an ostrich's egg.

The Ting glaze effect is also obtained by placing on the body a thin white slip and superimposing upon that a transparent film of glaze. The result is to produce a fine white surface with a " softness " very similar to that exhibited by the Ting glaze. Many of the specimens so glazed probably come from the factories of Tel:/ Chou which will be mentioned later, and of other districts in southern Chihli.1

During the Ming dynasty the traditions were continued, but the body of the ware was made of finer porcelain, and a more " glassy " surface is found. Many of the Ming reproductions, however, are very hard indeed to distinguish from Sung specimens, especially the imitative wares made towards the end of the Ming dynasty in the reigns of Chia Ching and Wan Li.

In the estimation of a very large number of collectors the early celadons hold the highest place. The green, blue-green, and green-grey tones displayed by the celadon wares never weary the eye and always harmonise with an artistic colour-scheme. Hence their universal popularity not only to-day, but in bygone ages ; specimens of celadon ware have been found in all parts of the world —Java, Sumatra, the Philippines, Borneo, India, Persia, Arabia, Egypt, and Zanzibar.AN INTRODUCTION

In Sung days the most important centre of celadon production was a place called Lung Ch`tian, in the province of Chekiang, where there were two brothers by name Chang. The elder brother potted vessels the glaze of which was crackled and which go by the name of Ko ware ; accredited specimens of this ware are scarce. But specimens of the art of the younger brother and of his school are not difficult to find ; we know of a number of wasters dug up on the old kiln-site which enable us to recognise the ancient descriptions recorded in Chinese literature.

The body is a grey porcellanous material which often exhibits a red colour at the foot-rim where it has been exposed to the fire. The glaze varies in colour from a definite green through shades of blue-green to a dove-like grey ; in all cases there is a softness of colour due to the fact that the glaze is not transparent. In the later Ming celadons a more " glassy " appearance is noticeable though the same range of colour tones is found.

The most prized celadon colour is an opaque blue-green or blue-grey which sometimes goes by the name Kinuta, a term applied to it by the Japanese and derived from a famous mallet-shaped' vase with a glaze of this colour.

Some of the most beautiful of the Sung specimens owe their charm entirely to shape and glaze effect, but others are decorated by ornament in relief or by incised designs.

A curious effect is found in the so-called tobi seiji, or spotted celadon, where irregular blotches of dark brown are set in the green glaze. A fine example is seen on Plate LXXII.

The celadons which have been found the world over usually consist of heavy plates and dishes or large vases and bowls ; these went in former days by the title martabani ware. The name is derived from the Gulf of Martaban on the shores of which lies the town of Moulmein in Burma. The ware was largely re-exported from this centre. In India these heavy plates are often called ghori ware ; a name derived from the town of Ghoor on the Persian-

Afghanistan frontier, and the seat of government of the Ghori Emperors of India. They are also called poison plates, from theTHE ART OF THE CHINESE POTTER

tradition that they possessed the property of neutralising the effect, or disclosing the presence, of any poison that might be contained in food placed on them.

A great many of these heavy celadon dishes and plates date from Yuan and Ming times when world trade with China was widely

developed. A characteristic feature is the broad unglazed ring, often red in colour, found on the bottom of the dish marking the place where the specimen was supported during firing.

A branch of the celadon family is found in the family called " Northern Chinese," a term embracing a group of wares the precise provenance of which is not at present known. The colour of the glaze is an olive green of different shades, and the ware is usually distinguished by a dark brown body and bold incised decoration. Wares of this type were made as early as the gth century as has been noted on a previous page.

Perhaps the ceramic factory with the longest continuous history in the world is that of Teti Chou in Chihli. Crockery Town, to give an English rendering of the Chinese name, is said to have commenced its ceramic existence in the Sui dynasty (589-618 A.D.), and it is still a flourishing manufacturing centre ; thirteen hundred years is a span of time of no mean order, a record in comparison with which only Ching-te Chen can compete ; and the wares produced from its kilns appear to have been of a similar character throughout its life.

We have no definite examples of pre-Sung date to which we can point, but specimens of Sung origin are easily found. The body is a grey stoneware tending towards a reddish brown colour, and the glaze varies in colour from white to black. The commonest examples are dishes, vases, and jars covered with a white or creamy glaze on which bold designs are painted in brown or black. The white glaze effect is achieved by means of a white slip with a transparent glaze superimposed. Another variety consists of black glaze with or without a design in brown upon it. This black glaze may or may not exhibit " hares fur " markings which are such a feature in the temmoku glazes described later.

The Tea Chou potter varied his effects by means of an incising tool, and we often find specimens in which the unfired glaze has been removed to form the design so that on firing the latter stands out as a bold relief on the exposed biscuit. In the white glazed pieces the slip may be etched away in a similar fashion so that the body shows below the transparent glaze in parts and the white slip elsewhere forms the design.AN INTRODUCTION

Though black and white, or brown and white, decorations are the usual embellishments of the Teti Chou ware, they are not the only ones. Painted designs in red and green upon a white ground are also found on ware resembling that of Teti Chou, and they constitute one of the few manifestations of polychrome decoration in the Sung dynasty.

Allied to the Te5 Chou ware, but probably executed at some other centre, are specimens with a reddish stoneware body and with painted or incised designs covered with a transparent blue or green glaze. The technique is so like that employed at Teti. Chou that these wares have been included in the Teti Chou family.

In the Ming dynasty the ware was similar and it is difficult to distinguish between Sung and Ming specimens, except perhaps in the type of design and the freedom with which it is executed. The post-Ming examples show considerable falling off in artistic qualities.

The wide range of technique employed at this centre and other allied factories is well displayed in Plates LXXVIII to XCII

Our next group of wares, though a comparatively new one in the experience of collectors, is perhaps the choicest of all the Sung porcelains. Very little has been written about them hitherto, and specimens have been hard to come by until recently ; even now they are difficult to obtain. The opening of tombs in Honan has brought to light a certain number of buried specimens, and these have whetted the collector's appetite for more.

The ware goes by the name of ying cleing yao which signifies a porcelain with a shadowy or misty blue glaze. The body is highly translucent in thinly potted examples and has a white sugary appearance. In other specimens the body, though made of similar porcelain, is much thicker and does not transmit light. The colour of the glaze varies from a white with a suspicion of blue in it to a pronounced light blue. The frontispiece to this album represents a choice example, and Plates XCIII to XCVII display other specimens.

When this ware first came to this country many years ago it was reported to have been found in Corea. The more recent specimens have been derived from Honan tombs. This latter origin is interesting because some colour is given thereby to the surmise' that these specimens may represent a type of Ju ware.THE ART OF THE CHINESE POTTER

Ju yao has always been spoken of in Chinese ceramic literature as one of the most famous productions of the Sung potters. Made at Ju Chou in Honan it ranks only second to the celebrated Ch`ai ware of which no authenticated specimen is known to exist. On these two types of porcelain the full battery of extravagant description and praise has been turned by the Chinese writers, and the literature teems with encomiums of them. " Blue as the sky after rain, clear as a mirror, thin as paper, resonant as a musical stone of jade," and phrases of this order are the tribute paid by the ancient connoisseurs. We are told that a similar type of ware was made in the districts of Tang, Teng, and Yao, on the north of the Yellow River, and there is no doubt that the minor Honan factories were employed on producing porcelain similar in character to that of Ju Chou. Further, a writer in i125 speaks of certain Corean wares as being like the " new wares of Ju Chou." These statements support the view that the recent specimens found both in Honan and Corea may be of the Ju type, though it would be rash to ascribe any of them definitely to the potters of the famous Ju factory in the absence of kiln-site evidence. In support of the theory that this ware is of the Ju type it may confidently be stated that the porcelain of which it is made is of finer quality and more delicately potted than any other of the Sung wares ; the incised designs which appear on some of the specimens are of a high order, and the general appearance of the best examples accords in large measure to the literary descriptions of Ju yao.

In marked contrast to the delicate potting of these porcelains is the heavy stoneware represented by the Chien yao, which is held in high esteem both in Japan and among Western collectors. The centre at which it was manufactured is Chien-yang in the province of Fukien. The body is heavy and black, and turns a rusty colour where exposed to the fire. The glaze is a lustrous black flecked with golden brown ; the terms " hare's fur " or " partridge markings " are given to these brown splashes from their similarity to the mottling of the tegument of these animals. The glaze is thick and terminates in heavy rolls or large drops short of the foot of the vessels, which almost invariably take the form of bowls. These bowls were used in the tea contests and tea ceremonies that had a great vogue in China in the past and still have in Japan to the present day.AN INTRODUCTION

The same kind of glaze was used at other factory centres upon a lighter coloured body ; many examples can be found which appear to have been potted at Tz`ii Chou, and no doubt many of the Honan factories made similar glazes.

The golden brown markings take several forms, being widely spaced or more closely aggregated ; while in some cases the whole surface of the glaze may be red-brown. In other instances the black glaze may have silvery drops on it resembling oil spots, and this effect is prized in Japan.

There is a third type' of temmoku bowl of which examples may be seen on Plates CII and CIII. The body is yellowish in colour, and the designs drawn in the glaze are of a fairly elaborate nature, birds, insects, and floral figuring being executed in a glaze of different composition from that surrounding the design.

The name temmoku (eien mu, or Eye of Heaven) was first given to a bowl, probably of Fukien origin, brought to Japan during the Sung period by a Zen priest from the Zen temple on the Tien mu shan (Eye of Heaven mountain) in the north-west of Chekiang. In later times the generic name of temmoku came to be applied to the whole category of wares of this type.

In the foregoing brief review of the wares made at the main centres of production during the Sung dynasty, we have drawn attention to the development of a finer type of body than that used in earlier periods. It is conceivable that the felspathic glazes then employed, requiring as they do a higher temperature for their manipulation and development, led to the further porcelainisation of the body and prepared the way for the still finer bodies employed in the Ming and later periods. If this be generally true, it must be remarked that the ying clang ware exhibits a body which, in some examples, is as fine as any subsequently achieved by the Chinese potter, and that a good white porcelain was already made in the Tang period.THE ART OF THE CHINESE POTTER

The glaze effects of the Sung potter show a marked advance on those of his predecessors and exhibit a considerable mastery of technique. But it is probably in his artistic sense that the Sung potter chiefly excelled. Both in the simple shapes he used and in the designs he executed there is a subtlety which is generally lacking in the art of his successor. The shapes may be heavily fashioned, they may be simplicity itself, but it is rare indeed to find an example of Sung workmanship that does not make some appeal to our senses.

The drawing on the vessels whether executed by an incising tool, or by relief ornament or by bold washes of glaze colours, is invariably distinguished in character. It was the result of a relatively few strokes, as a rule, and the design is always in keeping with the vessel on which it is portrayed. With the growth of knowledge, elaboration of technique was exhibited later, and science to-day may be able to repeat the glaze effects of Sung times ; but where the modern craftsman will fail is in the reproduction of the Sung drawing, unless considerable advances are made in artistic feeling in modern ceramic work.

The ideals of the Sung dynasty, whether in artistic expression or in philosophic thought, have always held a high place in Chinese estimation ; so far as Sung art is concerned, the West has accepted that view and will continue to do so.

With the coming of the Mings, the old factories, which had supplied the ceramic needs of the Sung and Yuan dynasties, receded into the background, and Ching-te Chen rose into pre-eminence.

Ching-te Chen, in northern Kiangsi, is the home of porcelain proper. It was probably the source of the white porcelain found in the gth-century ruins of Samarra, on the Tigris ; and in the Sung period it produced a white ware which carried on the traditions of the Ting.

Changing fashion in the Ming period decreed that the famous monochromes of the celadon class should give place to white porcelain decorated with pictorial designs in coloured glazes, in overglaze enamels and in underglaze blue ; and the only monochrome which appears with frequency among Ming porcelains is the pure white.

By far the largest Ming group is composed of the blue and white porcelain. It ranges in quality from the daintily fashioned palace pieces to the rough wares exported by land and sea to Western Asia and Europe ; and it is not less varied in the shades of the blue with which it is painted. The colouring matter is derived from cobalt ; but the blue produced by the native supplies of this mineral, if not laboriously refined, had a dull grey or indigo tone, and the most famous Ming blue was imported from a Mohammedan country, doubtless Persia. It is, in fact, known as Mohammedan blue. The supply of this material was irregular, but we know that it arrived in the Hsuan Te, Cheng Te, and Chia Ching periods. During the remaining reigns apparently no new importation of it was made. In use it was blended with the native cobalt in proportions varying according to the quality of the ware desired.AN INTRODUCTION

The Hsuan Te Mohammedan blue is extremely rare and even Chinese writers do not agree as to whether the prevailing shade was light or dark. But we have many examples of the Chia Ching blue which is of the dark violet tone seen on Plate CXLVIII. The more familiar Ming blues are usually tinged more or less with indigo; but even the least brilliant of the Ming blue and white porcelain is distinguished by a freshness and freedom of design ; and the skilful brushwork of the Ching-te Chen decorators is seen to the best advantage in this ware. The actual designs are largely derived from the patterns on silk brocades, but we hear too of designs painted by the Court artists and sent to be copied at the Imperial factory.

Another underglaze colour, for which the reign of Hsuan Te was specially celebrated, is the brilliant red derived from copper. This was used both as a glaze colour (i.e. in the glaze), or for painting individual designs under the glaze. Both types are illustrated on Plate CVIII. The successful development of this colour seems to have puzzled the potters after the Hstian Te and Ch'eng Hua periods, and we are told that they virtually abandoned it for a long time in the 16th century in favour of an overglaze red enamel.

The Ming polychromes, which include some of the most striking and decorative wares of the period, fall into two main groups—those with lead-silicate glazes or enamels applied direct to the biscuit, or body of the porcelain, and those with enamels painted on the white glaze. The former class is sometimes called " three colour " (san ts'ai) porcelain, the trio of colours being selected from the following—dark violet-blue, turquoise, aubergine (a purplish brown or brownish purple), yellow, green, and an impure white. But it should be added that the number of colours used was not always strictly confined to three. Some of the earliest Ming polychromes are decorated with this colour-scheme, and the designs are generally outlined by threads of clay after the manner of the cloisonné enamel on metal. Sometimes, too, the designs are carved or pierced in openwork or framed by incised or pencilled outlines. The three-colour ware with incised outlines is often found with the Cheng T8 mark, and that with outlines pencilled in brown with the Chia Ching, and occasionally with the Ch'eng Hua, mark. All these classes of polychrome are illustrated on Plates CX, CXV I, CXX, etc. ; and all of them, except the last, are frequently found in pottery as well as porcelain. The large group of porcelains with pencilled designs covered with soft enamels applied direct to the biscuit, though including a certain number of Ming specimens, belongs in the main to the succeeding dynasty.THE ART OF THE CHINESE POTTER

The other principal group of polychrome, that decorated with soft enamels painted on the white glaze, has the generic name of wu te ai, or five-colour ware, though here again the colours are not strictly limited to the number implied. They include green of several shades, yellow, tomato red, aubergine-purple, a composite black (formed by a wash of transparent green or aubergine over a dry brown pigment), and a turquoise green. This last is the usual Ming substitute for a blue enamel ; but if a true blue colour was desired, it was supplied by the ordinary cobalt-blue under the glaze. The Ming yellow is generally brownish or of amber tint ; the red, though thin, is opaque and tends to become iridescent.

The Ming potters were partial to openwork (ling lung) decoration which we find on a large scale on the early wine-jars and barrel-shaped seats. But the perfection of the pierced ornament is seen on the delicate little bowls, made at the end of the Ming period (see Plate CVII, Fig. 1), with sides pierced in fret patterns of unimagined fineness. This is the kuei kung (or devil's work) of Chinese writers, and it assuredly needed an almost supernatural skill to accomplish it. Combined with the ling lung work we often find daintily modelled reliefs, figures, and other designs, in unglazed biscuit. They are sometimes of microscopic fineness, at other times of moderate size and standing out in full relief. The biscuit in these porcelains was often overlaid with oil gilding applied on a red medium. Another decoration, remotely related to these biscuit designs, is traced in white slip on a coloured, or under a colourless, glaze. Plates CXIV and CXXXIII show good examples of this type.

The Ming monochromes, which as already stated are relatively rare, include celadon green, brown-black, and a variety of blues, besides the lead-silicate glazes and enamels which are used on the three-and five-colour ware, viz. green, aubergine, turquoise, and yellow. The porcelain made in the early Ming reigns is naturally very rare and precious to-day, especially that proclaimed by its fine execution to be Imperial ware. None is more highly prized than the finer types made in the Hsuan Te and Ch'eng Hua periods, the two classic reigns of the dynasty. The former of these reigns was noted for its " blue and white " and underglaze red ; and the latter for its underglaze red, and enamelled wares. A fair number of the larger and more stoutly constructed of the 15th-century porcelains is still to be seen ; but very few of them are in perfect condition. Such pieces were not preserved from their early youth in silk-lined boxes. They have had to stand the usage of many centuries and to pay the forfeit of their longevity. The 16th century is more fully represented in our collections, which include many fine specimens of three-colour ware with engraved designs and " blue and white " of the Cheng Te period, together with a great variety of Chia Ching porcelains. Both these reigns have a high reputation among Chinese connoisseurs. The surviving Wan Li wares are comparatively numerous, and, in general, display less refinement in material and manufacture. This is partly explained by the fact that the mines at Ma-ts'ang, which had supplied the best porcelain clay to Ching-te Chen, were worked out by this time. Apart from Ching-te Chen, a fine white porcelain was made at Te-hua in Fukien in the last half of the Ming dynasty. The Fukien ware is distinguished by a soft-looking, luscious glaze of great transparency, which blends very closely with the body material. In general it is milk white, or cream white, with a pinkish tinge in some cases ; and the texture of the glaze has been aptly compared with blancmange. It is the blanc de chine of old French writers ; but as its manufacture continues on the old lines to this day, it is very difficult—in many cases impossible—to distinguish the Ming productions from those of later periods.

Figure modelling was a speciality of the Fukien potters, and some good examples of this work are shown on Plates CIV to CVI, but it would be unwise to guarantee that they are all of Ming date.THE ART OF THE CHINESE POTTER

In addition to the porcelains of which most of the Ming specimens in this album consist, there was a vast quantity of pottery and stoneware made in the many factories scattered up and down the eighteen provinces of China. Much of this is classed as " tile ware," and indeed it includes roof tiles and architectural pottery which are often distinguished by finely modelled ornament and rich glazes. But the tile factories and miscellaneous potteries also produced many noble vases, fish bowls, figures, and groups, in which the three-colour glazes were applied to a pottery base with strikingly beautiful effect ; and one of the most attractive of the late Ming types are vases with a stoneware body and soft-looking turquoise, green, and aubergine glazes, such as those represented by Plates CXXVII and CXXIX. The provenance of these handsome vases has not been definitely ascertained.

Such then is the story, in briefest outline, of the development of Ceramic Art in China up to the early part of the 17th century. After that date potting technique may have been further elaborated and certain new glazes invented, but the art of the Chinese potter never reached a higher plane than in the best of the early periods. Indeed the later potters often devoted their skill to the reproduction of the older types. It may be that part of this tendency was due to the proverbial Chinese veneration of the past ; but in any case these imitative efforts were not conspicuously successful. The simple beauty and the freshness of the earlier wares are their chief distinction, and they do not suffer from the fussiness which is often noticeable in the work of the i8th-century potters. Most of our readers are familiar with the finer examples of i7th- and i8th-century porcelain, and they can form their judgment on the truth of our statement from the illustrations which follow.

Leave a Reply